In the current controversies surrounding use and development of Edinburgh’s public spaces, particularly green spaces, it is sometimes tempting to think we live uniquely in a time of moral slippage and civic decline.

How much better it would be if we could return to a more decorous period, when people knew how to behave and the city’s parks were places of sacrosanct amenity.

Today, Spurtle looks back and basks in the glow of Princes Street Gardens’ 19th-century golden age.

NAE MUCKIN’ ABOOT, Edinburgh Evening Courant, Thursday 11 September 1851.

A report was read from the Lord Provost’s Committee, embodying certain regulations which they proposed the Council should enact for the protection of East Prince’s Street Gardens. These regulations, in so far as they related to the public, were as follows:—

1. The gates will be opened, during summer, at six o’clock A.M.; and during winter at sun-rise. They will be closed at sun-set.

2. No children will be admitted except under the care of a grown-up person, who shall be responsible for their conduct.

3. No intoxicated or disorderly person will be admitted. No smoking allowed. No dogs admitted.

4. No persons carrying burdens, or packages of any kind, will be admitted.

5. Persons detected pulling flowers, or injuring shrubs, trees, or buildings, will be committed to the custody of the police. Persons carrying flowers will not be admitted.

6. Visitors are requested to keep the walks and to protect the grounds.

The report was unanimously approved of, and the regulations confirmed. The Council then adjourned.

ABUSING A PRINCES STREET GARDENS PRIVILEGE, Edinburgh Evening News (Tuesday 2 August 1892)

It will be remembered that about three weeks ago a new entrance was made into the Princes Street Gardens at the Mound. This was done chiefly at the instigation of the Trades Council, who took the step in the interests of the people—especially the young people—resident in that part of the city. Unfortunately what might have been a great boon is likely to be greatly abused, and measures will have to be taken to prevent the defacement of the garden.

It seems that at the entrance in question a large number of boys and girls are in the habit of gathering and sliding down the hill. So much has this been done that at the spot the grass is nearly all worn away and the appearance of the hillside spoilt.

With a view of putting a stop to this the convener of the Parks Committee has put an extra man on the place to prevent this and other conduct on the part of older persons, which is described as reprehensible. No one will be prevented from going into the garden and using it to the full, but anyone defacing or injuring the place, or conducting themselves in an unseemly manner will be rigorously dealt with.

It is hoped that the public will co-operate, and prevent the abuse of what must undoubtedly be a great boon. Yesterday the gate was entirely closed, the reason being that some mischievous persons filled up the key hole with sand, making it impossible to open the gate. No locksmith could be got owing to the trades holidays, but to-day the gate will be opened again.

AUTOCRAT OFFICIALS, Edinburgh Evening News, Wednesday 29 July 1891

It is now beyond the shadow of a doubt that the correspondent was right, who in our columns a week ago, declared that the victory gained by the Corporation had been practically thrown away during the course of negotiations between the rival engineers.

At the meeting of Town Council yesterday, Mr Pollard asked as to the truth of the assertion that the [railway] company had got a slice of 3 feet in width on each side of the Gardens.

Mr Auldjo Jamieson’s reply was so much rhetorical sawdust. Instead of frankly admitting that Mr Cunningham, the city engineer, had played the part of a master rather than a servant, Mr Jamieson plaintively sheltered himself under the plea that the deputation being in the hands of the engineer, could not help themselves.

Was there ever a more humiliating confession of weakness? The deputation was not in the hands of the engineer. Was it then part of the engineer’s duty to give the company land enough to provide for the reconstruction of Waverley Station? Had he the right to give effect to his private views in the teeth of the Chairman’s express deliverances?

In reply to the question of Mr Balfour Browne, during the proceedings before the Parliamentary Committee, in regard to the concessions to the company, the Chairman said: “We gave them no land between the Waverley Bridge and the Mound for the purpose of the station at all; it was only for the purpose of the four lines; that was our decision.”

In the face of emphatic declarations of this sort, where was the need for the wrangling which Mr Shelford describes in his letter? Mr Shelford says: “The decision of the Committee was very favourable to the Corporation, but it was accompanied by the troublesome obligation to agree with the company as to the amount of land to be taken for the four lines. The company refused absolutely to consider any other plan but their own, and there was no hope of agreement upon any other basis.”

But the city’s representatives could have stopped all wrangling by simply referring the company to the explicit declarations that only as much land could be given as would suffice for the four lines.

It is to the credit of several members of the deputation that they saw the bog into which Mr Cunningham was leading the city. This is made plain by the memorandum which was read by the Lord Provost. From it it is clear that several members of the Corporation were bent upon sticking by the Committee’s decision: “On being referred to, Mr Shelford was prepared to take the view of the Corporation, holding that the plan of the station could be and ought to be accommodated to the ground. Mr Cunningham persisted in regarding the plan as one to be adhered to, and in that view said he considered the space arranged for between the engineers indispensable to the company and what we ought to concede.”

Mr Cunningham was asked by the chairman in regard to the gardens, and he stated his opinion unmodified by what had previously passed. The chairman accepted his decision as representing the Corporation, who were therefore refused a hearing.

The city has to thank Mr Cunningham for converting what was a substantial victory into an inglorious defeat. The city need not have been dragged into this deplorable mess if the deputation had led Mr Cunningham to understand that he was a servant, not a master. His duty was to co-operate with the Corporation in giving effect to the decision of the Parliamentary Committee. He had a right to air his views in the witness-box about the need for more land for the reconstruction of the station; he had no right to galvanise them into life after the decision, and make the Corporation stand sponsor to them.

It is time the ratepayers were giving forth no uncertain sound about the manner in which the city’s affairs are bungled through being left in the hands of autocrat officials. The representative system is a mockery if the interests of the city are to be taken out of the hands of the people’s representatives and given to irresponsible officials.

Autocracy is bad, but the autocracy of professional advisers is peculiarly objectionable. They labour so much in the subterranean region of diplomacy that it is necessary to take their advice with large allowance for the personal equation.

For more on this story see:

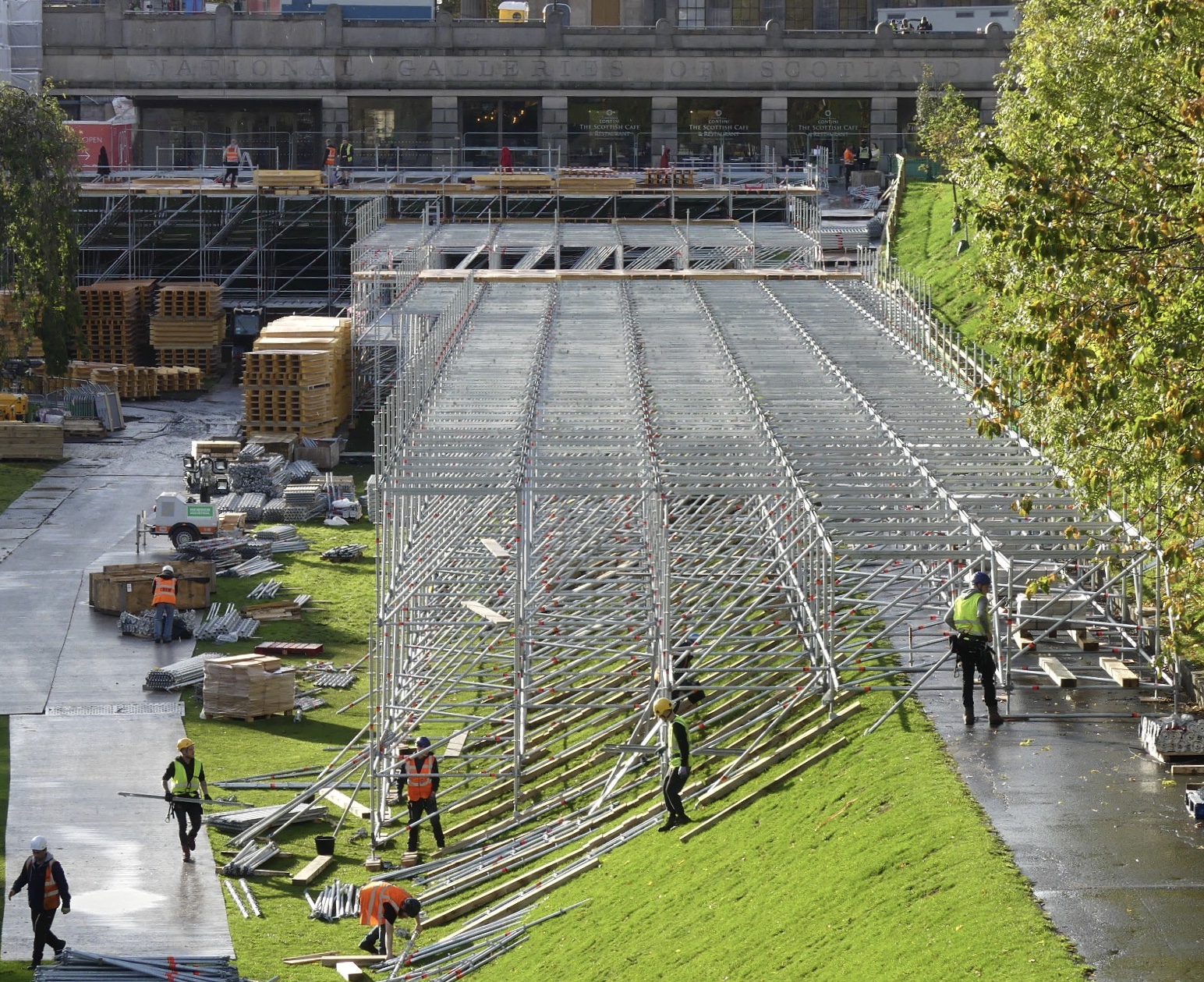

Scaffolding in the park – Council blusters (25.10.19)

Planning flaw threatens Winter Festival food and drink (28.10.19)

East Princes Street Gardens – room for improvement (29–30.10.19)

Underbelly moves on PAN application (1.11.19)

East Princes Street Gardens (12.11.19)

----------