FASHION, FRIPPERIES, AND YOUNG LADIES' CHANGING EDUCATION

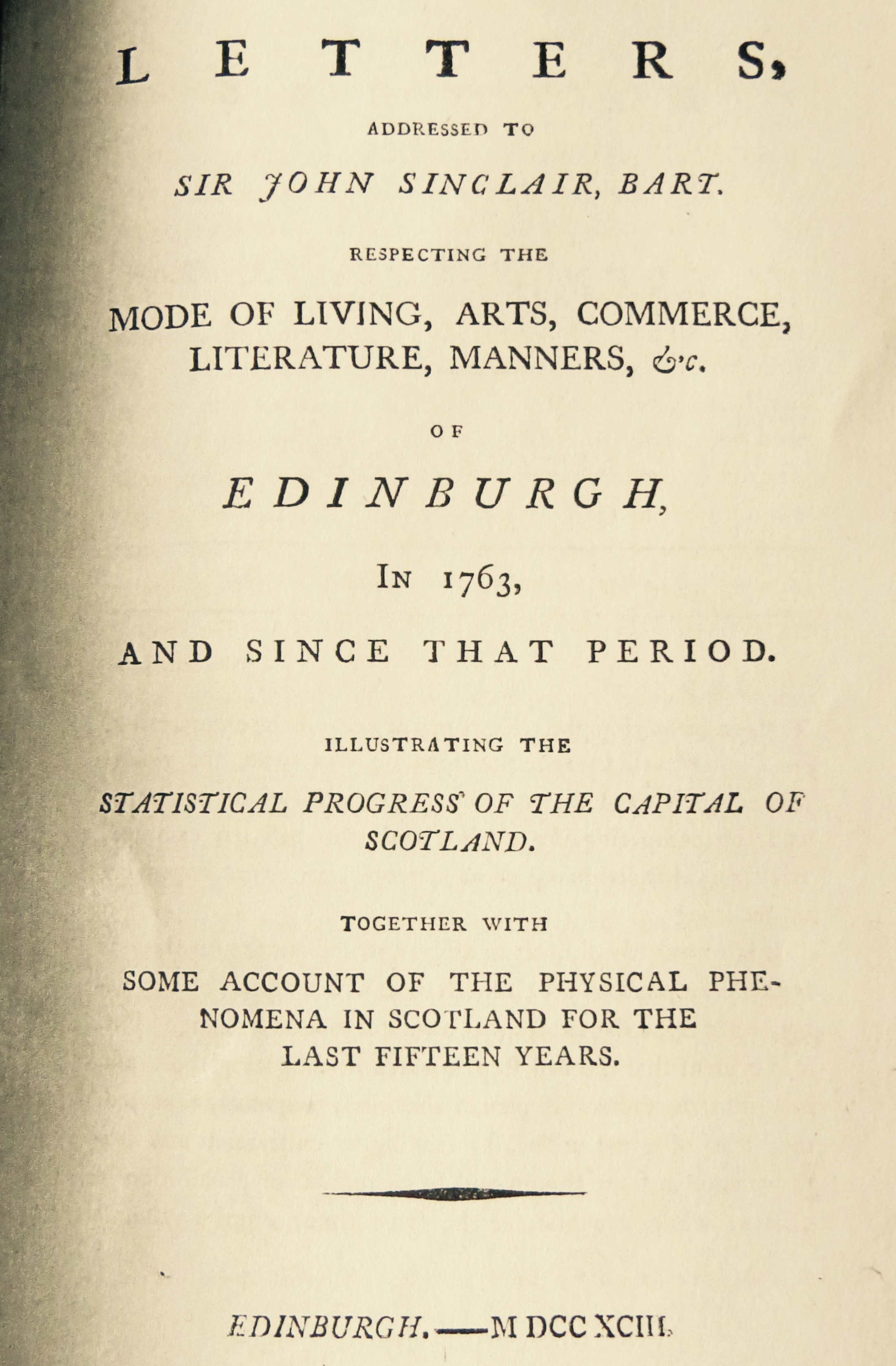

In the Statistical Account of Scotland’s section on Edinburgh, there appear many gleanings from letters addressed to the original editor, Sir John Sinclair, in 1793.

Parts of these are of great interest to economists and historians, others to the idly curious like Spurtle.

The following extracts are reproduced unedited and in full:

In 1763 — There was no such profession known as a Haberdasher.

In 1783 — The profession of a Haberdasher (which includes many trades, the Mercer, the Milliner, the Linen-draper, the Hatter, the Hosier, the Glover, and many others) was nearly the most common in town, and they have since multiplied greatly.

In 1763 — There was no such profession known as a Perfumer: Barbers and Wigmakers were numerous, and were in the order of decent burgesses: Hairdressers were few, and hardly permitted to dress hair on Sundays; and many of them voluntarily declined.

In 1783 — Perfumers had splendid shops in every principal street: Some of them advertised the keeping of bears, to kill occasionally, for greasing ladies and gentlemens hair, as superior to any other animal fat. Hairdressers were more than tripled in number; and their busiest day was Sunday. There was a professor who advertised A Hair-dressing Academy, and gave lectures in that noble and useful art.

Gentrification and retail expansion advanced hand in hand like chickens and eggs. With them came a change in the educational accomplishments of young ladies.

In 1763 — In the best families in town, the education of daughters was fitted, not only to embellish and improve their minds; but to accomplish them in the useful and necessary arts of domestic economy. The sewing school, the pastry-school, were then essential branches of female education; nor was a young lady of the best family ashamed to go to market with her mother.

In 1783 — The daughters of many tradesmen consumed the mornings at the toilet, or in strolling from shop to shop, &c. Many of them would have blushed to have been seen in a market. The cares of the family were devolved upon a house-keeper; and the young lady employed those heavy hours when she was disengaged from public or private amusements, in improving her mind from the precious Stores of a circulating library; — and all, whether they had taste for it or not, were taught music at a great expense.

In 1791 — There is little alteration. Every rank is eager to copy the manners and fashion of their superiors; and this has in all ages been the case. Of what importance, then, is correct and exemplary manners in the higher ranks to the good order of society!

We shall turn soon to the changing accomplishments of young men at this period. It will not make for pretty reading.

Sir John Sinclair (ed.), 1975, The Statistical Account of Scotland 1791–1799, Vol. 2 The Lothians, with a new introduction by T.C. Smout (Wakefield: EP Publishing).