It’s hard to imagine – looking at scenes like these, captured yesterday – that waters so close to home can sometimes turn fatal, even in summer.

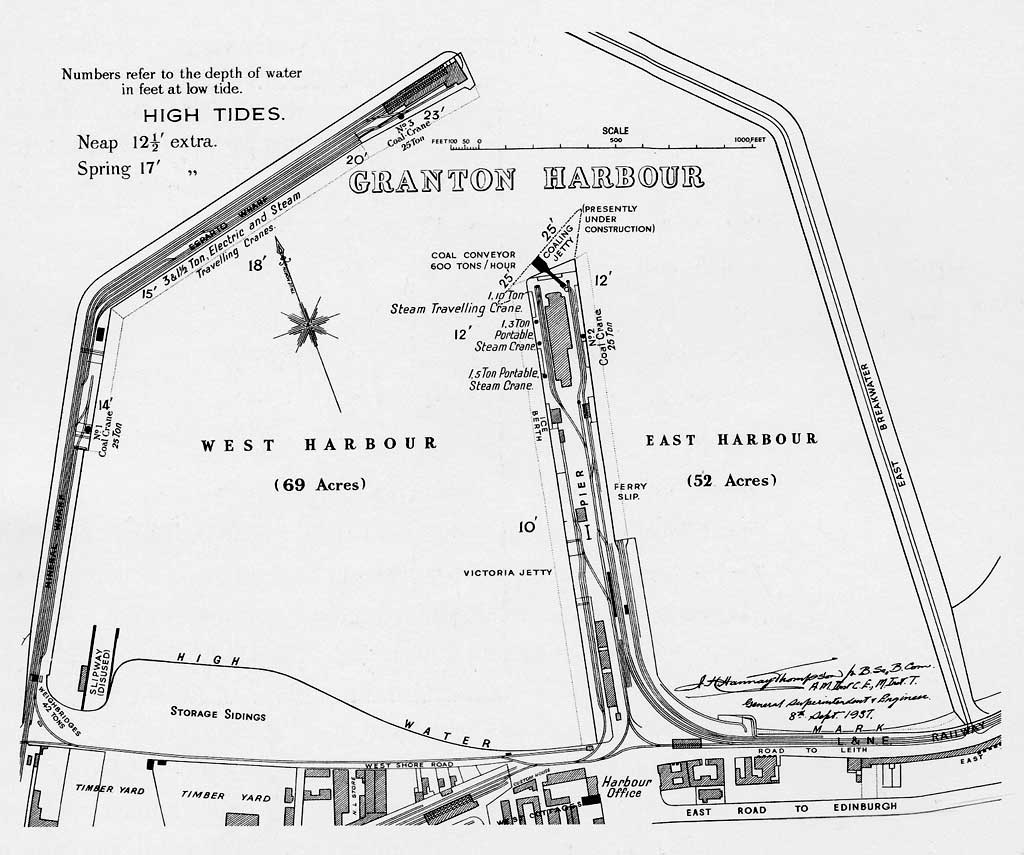

Such was the case on Saturday 20 June 1936, as yachts competed in the Royal Forth Yacht Club’s regatta at Granton Harbour.

In the last race of the day, five yachts made for the West Gunnet buoy in a strong north-easterly wind and heavy swell. All were struggling to complete the course, and another had already turned back.

Flying spray obscured the yachts from each other, and on the shore the commodore and boatmen retreated from the now dangerous breakwater and attempted to follow the race from Granton’s middle pier. A haze over the sea made this impossible.

Ian M’Millan of Laverock Bank was aboard the Daydream as it tacked towards Leith. Although mostly intent on his own safety and that of his fellow crewmembers, he noticed another competitor – the small 5-ton Jabberwock – tacking across their stern and bearing northwards. A sudden heavy squall carried away the Daydream’s mainstay. Its jib shot shortly afterwards.

‘For about 20 minutes,’ M’Millan told the Evening Dispatch later, ‘we were so busy repairing the damage that we were paying no attention to anything else.’ When they looked around and could no longer see Jabberwock, the Daydream’s crew assumed she had run for Granton or Leith.

Only when they themselves reached Granton did the Daydream crew learn that Jabberwock had not returned. Urgent telephone calls were made to Leith and ports along the shore of Fife. No-one had seen her.

Unhappy search

A search was launched, and before long the pleasure steamer Fair Maid discovered a sail protruding a foot from the water roughly a mile out of Granton.

Closer examination revealed that all the sails of the sunken yacht were set. She lay in about three and a half fathoms of water at low tide. There was no sign of any of the crew. Probably the same squall that had carried away the mainstay of the Daydream had struck Jabberwock and flattened her out. Having a heavy keel, she would have gone down instantly.

A diver searched the vessel the next day, and no bodies were found within. All had evidently been swept overboard, and it was recalled that they had been wearing oilskins from which it would have been very difficult to free themselves once in the water.

Remaining races scheduled by the Royal Forth, Forth Corinthian, and Almond Yacht Clubs for later in the week were immediately cancelled.

Lost at sea

Jabberwock’s owner and skipper was John G. Dick (57), an experienced and careful sailor who had owned the boat for around 20 years. He had practised as a dental surgeon at 32 Royal Circus since the early 1900s.

Also aboard was the recently graduated Dr John Scott of Peebles, who had been about to take up a job as house surgeon at the Northern Infirmary, Inverness. Although a keen sailor, unlike the others, he had not previously sailed on Jabberwock, He had only turned up on the day with the intention of being a spectator, and was invited aboard at the last moment.

The loss of 25-year-old Ronald Mitchell, of Crewe Crescent, was described by the Evening Dispatch as a particularly ‘pathetic feature’, since he left behind a young wife and newborn child. He had been employed as an Edinburgh printing firm’s traveller.

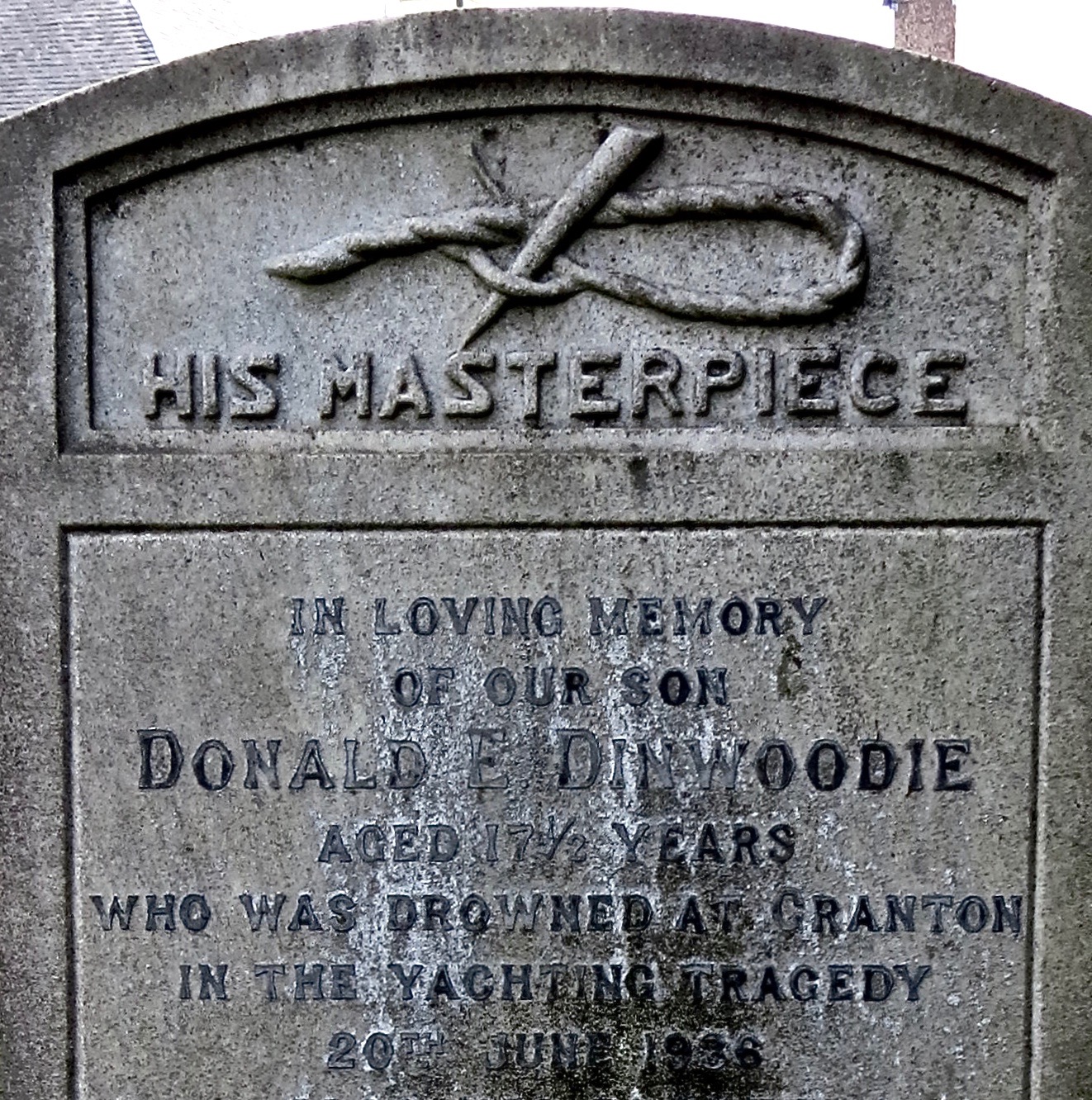

Finally, the paper addressed the ‘skilful yachtsman’ Donald Dinwoodie (17), a sailmaker and rigger with his father at Granton Harbour and resident in Lower Granton Road:

It was at first thought that one of the four people on board Jabberwock was Mr Duncan Moodie, a young local man, but it was learned later that he had been prevented from joining the crew by a previous engagement to take part in a cricket match. Mr Moodie had, on a number of previous occasions, accompanied Mr Dick on Jabberwock.

It was probably Mr Moodie’s place that was taken by Donald Dinwoodie, who had been asked earlier to join the crew of another yacht but had declined.

[Granton Harbour, 1937. © Reproduced with acknowledgement to Buccleuch Estates and Argyll Publishing.]

Father baffled by sinking

Monday’s Scotsman paraphrased an interview with Donald’s father John the day before:

… Donald had asked him if he thought he should go out with Jabberwock, and had replied that the weather was not very good, but he could please himself about going. Ultimately, Donald, who in the past six or seven years had been frequently out with yachts and was very keen on yacht racing, decided to go aboard Jabberwock for the race. Mr Dinwoodie, senior, remarked yesterday that he did not consider the weather was really bad when his boy spoke to him. It had been worse a fortnight ago when racing took place.

Despite John Dick’s reputation as a cautious skipper, some in Granton speculated afterwards that Jabberwock had been carrying too much sail for the conditions.

On Tuesday, with none of the bodies yet recovered, a Scotsman reporter interviewed John Dinwoodie in person. Three more of his sons were at sea, Dinwoodie explained, unaware of their brother’s disappearance:

I cannot understand about the Jabberwock. She was an excellent yacht, and although a heavy sea was running on Saturday, it is all a mystery how it happened. … He has always been so keen about yachts, and has spent all his time down here near the water. Even when he was a tiny chap, the yachtsmen used to take him out—sometimes wrapped in a sail sheet. They looked upon him as a mascot.

Recovery of the bodies

On Thursday 25 June, during operations to salvage the boat, a retired trawl skipper and Lower Granton Road resident brought Donald’s body to the surface using a dragging line. The Scotsman reporter, who was present, noted:

The body was clad in the yellow oilskins which the wearer had donned just before starting in Saturday’s race. It was recovered about 100 yards east of the wreck. Dinwoodie was the only member of the crew of the Jabberwock who was unable to swim, and this probably explains why his body was found so close to the yacht.

John Dick’s body eventually came ashore near Laurieston Castle on 29 June, and that of Scott was found floating in the sea just off Inchmickery the next day. The circumstances in which Ronald Mitchell’s remains were found are unclear, but he was interred at Piershill Cemetery on 8 July in a ceremony attended by Dinwoodie’s father.

The unfortunate young Donald E. Dinwoodie is recalled with love and concise, unflinching clarity on a headstone in Rosebank Cemetery.