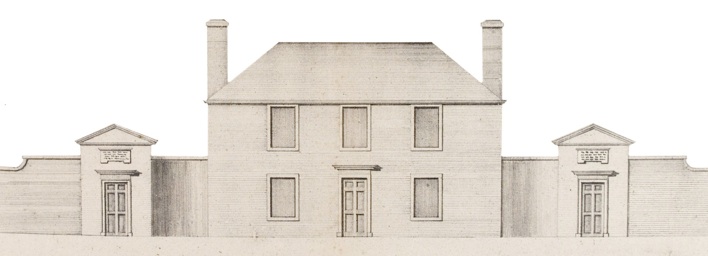

It is very exciting to see Botanic Cottage, once semi-derelict on Haddington Place, now emerging restored, extended and improved in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

As part of its painstaking reconstruction, the walls on either side of the former Leith Walk frontage have been rebuilt.

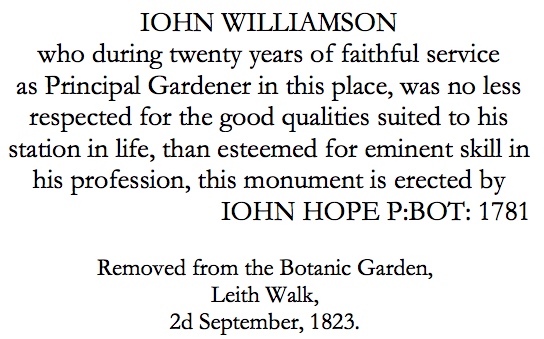

Above the gate on today's west side, an original memorial plaque to an early principal gardener (PG) – John Williamson – has recently been returned. (It was removed from its original site when the Garden transferred to Inverleith in 1823 leaving Botanic Cottage behind.)

Commissioned by Professor John Hope, Regius Keeper from 1761–86, it is a rather touching mark of of his professional esteem for a colleague who had died in 1780. It is likely to have been designed by the architect James Craig, and is known to have cost £2 17s 8d.

The inscription – at once warm and heavily class-inflected – reads:

Perhaps wishing to convey an impression that everything was rosy, the plaque made no mention of how Williamson had died.

A practical gardener

Williamson preceded Hope at the Botanic Garden by a year, arriving there as PG in 1760 with experience of similar work at the Abbey and Town gardens in Edinburgh.

He and his family were the first residents of Botanic Cottage, and here he rendered practical administrative assistance to Hope before, during, and after the professor’s lectures in the same building.

At other times, under Hope’s overall supervision, he managed ongoing experiments into transpiration, plant growth, the movement of sap, the polarity of branches, transpiration, hybridisation, and the relation of the parts of the flower to the formation of seeds.

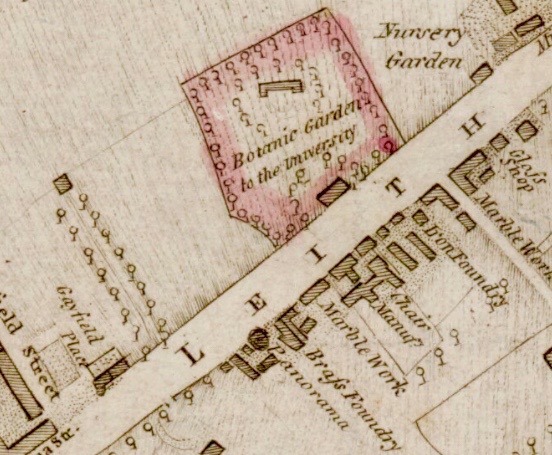

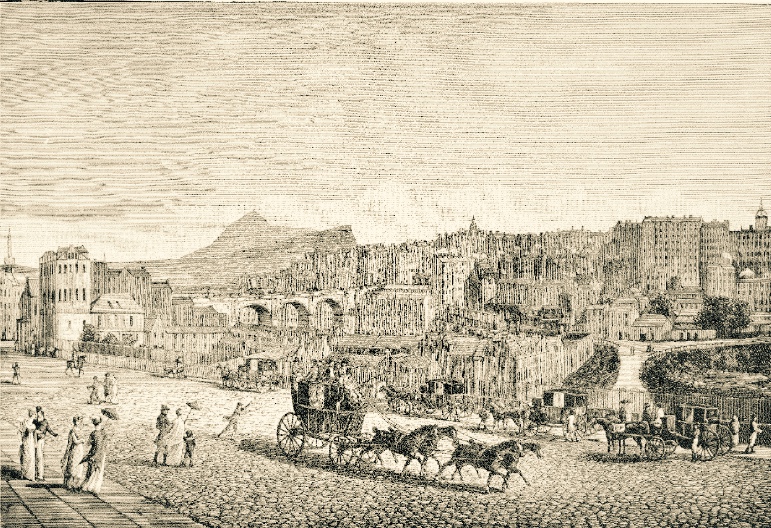

Williamson was widely applauded for his contribution to the Botanic Garden’s successful move in 1763 from Trinity Hospital and Holyrood to the 5-acre site extending north-west from Leith Walk across today’s Hopetoun Crescent.

His was a responsible job, for which he was remunerated to the tune of £25 per year.

A parallel career

Somewhat surprisingly, Williamson almost doubled that sum by working simultaneously as an exciseman (Customs official) in Leith. As a land carriage waiter, his appointment was a relatively junior one, involving the onshore search and checking of imported loads against manifests, and he would have made money by charging on a job-by-job basis to top up an otherwise fairly nominal salary.

Fletcher and Brown (1970) speculate that he was often in the port on Botanic Garden business, collecting or despatching specimens, for example, and so established an understanding of people and practices there.

It seems equally plausible, though, that Williamson would have exercised his duties in or around Pilrig, at the 'Gates of Edinburgh'.

Whatever its exact responsibilities and location, this aspect of his career was to cost him his life.

The ugly side of smuggling

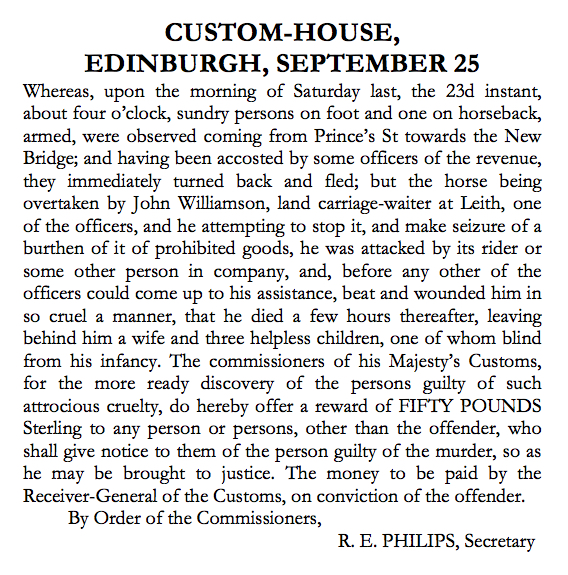

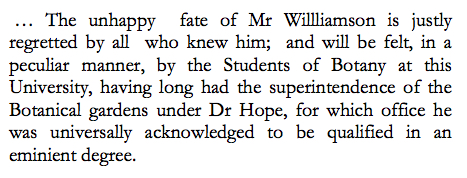

On 25 September 1780, the Edinburgh Evening Courant printed an advertisement. It reported shocking events that had occurred on Princes Street two days earlier:

The Caledonian Mercury carried the same piece, but supplemented it elsewhere as follows:

This was a turn of events which contemporary Edinburgh citizens found profoundly disturbing. The advertisement continued in various prints for another month.

The threat to law and order was one thing. The loss of Williamson was another. The eminent physician and academic Andrew Duncan, in his wide-ranging Medical Commentaries for that year, specifically mentioned the event, noting that: 'Great knowledge of his profession, singular dilligence, and amiable manners, made his death universally regretted, and considered as a public loss' (1783: 366).

Obscurity at last

It is not clear (to me, at least) exactly what happened next. I have yet to find a parish record of Williamson's death (which might clarify his age at the time), or the location of his grave. I've found no trace of his murderer(s) being caught, or of how his widow fared afterwards

Noltie (2011) claims Professor Hope later employed Williamson’s daughter Agnes as an illustrator. In 1787 she married another of Hope's illustrators Angus Fyfe, The marriage register describes him as a surgeon. Nolte says Hope also aided Williamson's sighted son Samuel with his education, and that the latter found work as a surgeon with the East India Company. Nolte's sources are not given.

This is a work in progress. If any reader can add details, we'd be delighted to hear from you (see update at foot of page). —Alan McIntosh

For background on this story, see:

http://www.broughtonspurtle.org.uk/news/botanic-cottage-project

and

http://www.broughtonspurtle.org.uk/news/stones-speak-rediscovering-botanic-cottage

Sources

Caledonian Mercury, 25 September 1780.

Duncan, A. (1783) Medical Commentaries, for the Year 1780 … , 2nd edn (London: Charles Dilly).

Edinburgh Evening Courant, 25 September 1780.

Fletcher, H.R. and W.H. Brown (1970) The Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh 1670–1970 (Edinburgh: HMSO).

Grant, F.G., ed.. (1922) Register of Marriages for the City of Edinburgh 1751–1800 (Scottish Record Society).

Noltie, H.J. (2011) John Hope (1725–1786): Alan G. Morton's Memoir of a Scottish Botanist, new and revised edn (Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh).

---------------------

Update

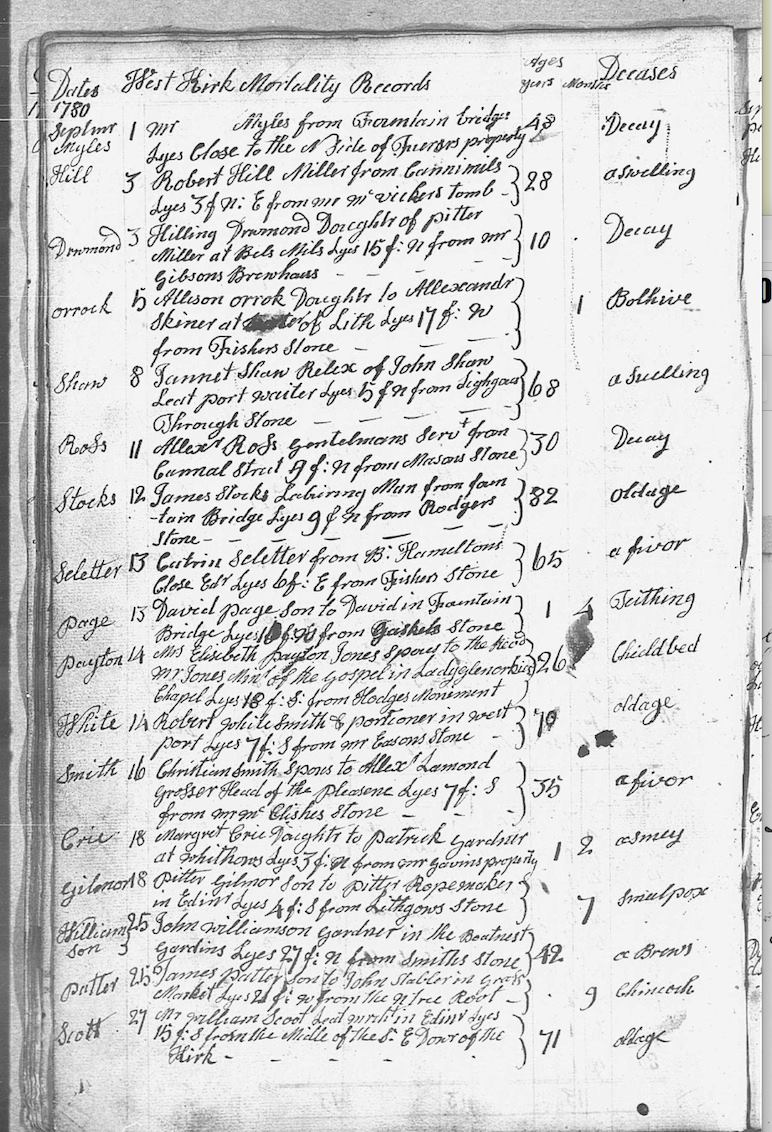

22 July: Many thanks to reader Judy Olsen who contacted us today with a very interesting discovery. Using the Scotland's People website, she accessed the recently added Mortality Records for Edinburgh West Kirk (St Cuthbert's at the foot of Lothian Road). There she found an entry for John Williamson. It lists him as a 'Gardner in the Botanic Gardens', and shows that he was interred on 25 September 1780 (presumably in an unmarked grave) 27 feet North of Smith's stone. His age is given as 42, and the cause of his death 'a brawl' or possibly 'a brews'.