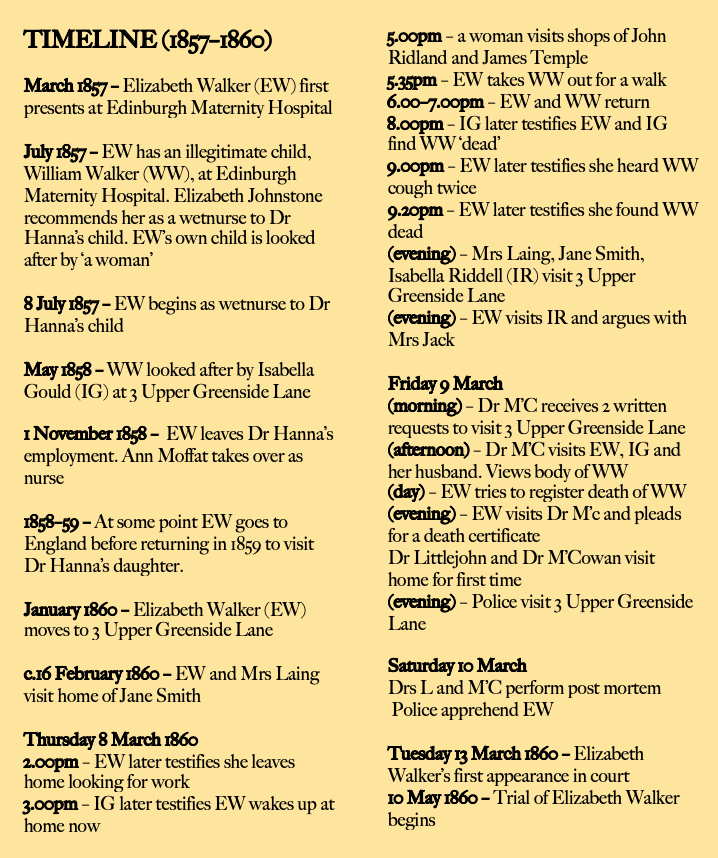

1860

CHILD MURDER

Elizabeth Smith or Walker, residing in Upper Greenside Lane,[1] was placed at the bar charged with administering a quantity of comrise sublimate[2] or other poison to her son aged two years and two months on Thursday last, in consequence of which the boy died immediately or soon thereafter, and was thus murdered by the said accused.

It appears that the accused had been up till a recent period employed as a servant, and during that period had given out her young son to nurse. For a short time back, however, she had been out of service, and has resided with the family in Upper Pleasance,[3] who had taken charge of her infant.

The child, which was thriving and well, was taken out by its mother for a walk on the Thursday, and on her return it turned sick, commenced to vomit, and died in about a quarter of an hour afterwards. The accused was remitted to the proper authorities to allow of the necessary investigation being carried out, and we believe that in the meantime a post-mortem examination of the body has been made.

Caledonian Mercury, 13 March 1860

[1] SR Births lists Elizabeth as being born on 2 April 1827 in Glasgow, St Andrew’s, Lanark. Her parents were Peter Smith and Elizabeth O’Donnell, and they were Catholic. I have found no record in Scotland of her marriage or death in Scotland. SR Deaths 685/2 327 gives William’s address as 3 Upper Greenside Lane, and says he was 2 years and 9 months old at the time of his death (not 2 years and 2 months as given in the article). The cause was ‘poisoning by nitre or saltpetre’, and he was buried in Newington Cemetery. His mother Elizabeth was described here as a domestic servant.

[2] This is perhaps a typesetter’s misreading of ‘corrosive sublimate’ – the lethal chloride of mercury.

[3] ‘Upper Pleasance’ is another mistake in the original article. The address was 3 Upper Greenside Lane.

*****

HIGH COURT OF JUSTICIARY. The High Court of Justiciary resumed yesterday morning—The Lord Justice-General, Lord Deas, and Lord Neaves presiding.

MURDER IN LEITH WALK.

Elizabeth Smith or Walker was charged with the crime of murder, in so far as on the 13th of March last, in or near Upper Greenside Lane, Leith Walk, she did wickedly and feloniously administer to, or cause to be taken by, William Walker, her child, then between two and three years of age, a quantity of nitrate of potash, or nitre, in consequence whereof the said child suffered severe illness, and died on the same day, or soon thereafter, and was thus murdered by the prisoner.

The prisoner pleaded not guilty. The Solicitor-General and Advocate-depute Donald Mackenzie conducted the prosecution; and Mr Morrison and Mr Macdonald, along with Mr Meikle, appeared on behalf of the prisoner.

Isabella Gould or Innes was the first witness examined by the Solicitor-General. She deponed—I am the wife of Alexander Innes, tailor in Greenside Lane, near the head of Leith Walk. I know the prisoner; she had a child, a boy, when with me. It went under the name of William Walker.

It came to live with me a few weeks before Whitsunday, two years ago.[4] It was the prisoner who placed the boy with me. She said to me when she left the child that she was a widow left with two children.[5] She told she had had the child in her widowhood. She continued to live in Edinburgh after that, and also at Piershill. She came to live in my house, I think, in January last. We have a kitchen and one room. I took charge of the child after she came to live with me.

She never was in the habit of taking the child out. It was a delicate child when I received it; but it grew better, and was able to play about the doors as other children. He called his mother aunt, and me “ma.” I have heard her say that she wished her child away, and I think she did not care for him living.

The child died on the 8th of March. He was in good health that morning, and played about the doors as usual. The prisoner rose that day, I think, about three o’clock. It was her usual habit to lie in bed the greater part of the day, and she went out in the afternoon to the institution for situations for servants, as she said.[6] I do not think she went out that day before tea, but I don’t recollect. I remember of the boy coming into his tea that afternoon, quite well. Prisoner and her boy were at their tea both together, and she complained he was eating too much. I offered him another piece, but she said, “Let him eat what he has got.”

He was sitting near the fire, and I noticed that he had a flushed face, which he had not when he came in. I remarked that he had a very flushed face, and she said that she would take him out and give him a walk. That was the first time that she ever took him out alone. When she proposed taking him out, he said, “Not take me out, aunty; leave me with ma.’’ She did take him out, twenty-five minutes to six o’clock. His mother brought him back between six and seven o’clock.

When she brought him in he began to vomit, and had also a bowel complaint. He was quite stiff and cold when he was brought in, and I was quite shocked with the condition in which he was. I was trying to warm him at the fire, when she took him and undressed him, and he was put to bed; but he would not warm. He vomited two or three times before he went to bed. He had four attacks of the bowel complaint.

I ordered her to go for a doctor, as I was alarmed; and I said to her, “If you do not go for the doctor, I will wrap him in my shawl and take him to the apothecary’s shop at the head of Leith Walk;”[7] but prisoner said, “You’re daft, he’ll be better tomorrow.” She refused to go for the doctor; and on proposal to bring in the neighbours, she said, “You’ll bring none of the neighbours in here.”

My husband was alarmed. This conversation about the neighbours took place after the boy was put to bed. I said to prisoner, “You must go for a doctor; the child is dying;” and added, “what have you done to Willie, have you poisoned him?” The prisoner replied, “I just told him that he would neither see his mammy nor his daddy again.” The boy lay quietly after I put a hot cloth to him. He was in the back room, and I was in the kitchen. I went and looked at him occasionally. It was about eight o’clock that the prisoner and I went to the bed and found the child dead.

She said, “Oh! he’s dead.” I was greatly alarmed. She said nothing further, but hurried on with the preparation of the things for his funeral.

She dropped only one tear, that I saw. I told my husband to go for a penny worth of castor oil and bring the doctor; but she said that he need not do so, as he would be better to-morrow. My husband got the castor oil, but the boy was too sick to take it. The child vomited upon my floor; and on the child being put to bed, prisoner washed the whole floor. She had never done so before, except on one occasion, after washing her own clothes. She emptied the slops herself.

All this took place before the child died. I never had saltpetre in my house. I called in some of the neighbours after the child was dead. Drs Littlejohn and M’Cowan came on the Friday,[8] and both opened the body of the child on Saturday. Shown a shawl, and recognised it as her own. Prisoner sometimes put it on. I am sure she did not have it on any time on the Thursday. I am sure the child was not out of the house after eating his tea till she took it out that night.

Prisoner said that the child had affronted her on the street, as he had vomited when she was out with him. She said that he had vomited orange-peel. The police came first to my house, I think, on the Friday evening. The prisoner was out in the course of the day trying to register the child, but she could not get it done without the doctor’s line. She was in when the police came, and also when the doctors examined the body on Saturday. Before she was taken away she told me to remember to tell that the boy had a flushed face. This was after the body was examined by the doctors. Shown a bundle of clothes which the boy had on that day.

Cross-examined by Mr MORRISON—The boy was a great favourite in the neighbourhood. When I got the child first, I remember the prisoner told me take the child to the doctor, as he was delicate. I think she kissed the child two or three times when she was parting with him. I was paid honestly for the child. When the prisoner told me that she had said to the boy that he would not see his mammy or daddy again, I did not think much of it.

Alexander Innes, tailor, husband of the last witness, corroborated her testimony in the general particulars as to the state of the child on the day of his death.

John Paton Ridland, grocer, Hart Street, deponed[9]—A woman came into my shop on Thursday, 8th March, about five o’clock. She did not come straight forward like an ordinary customer, and did not seem to have her mind made up as to what she wanted. I saw no child with her. She asked me how I sold saltpetre.[10] I said I had none. She asked where she could get it, and I told her Mr Temple’s above me. She then asked how it was sold, and I told her it was a cheap commodity, and was sold at halfpenny an ounce. Nothing else was said. I think the prisoner bears a strong resemblance to the woman. When I first saw her in the Fiscal’s office, to identify her, I thought I recognised her voice.

Cross-examined—l said when first shown her, that she did not appear to be so tall as the woman who came to my shop, but on seeing her a second time with a shawl on, I thought her appearance was more like the woman.

James Temple, grocer, Union Place, deponed[11]—I remember a woman coming into my shop in the evening, about five o’clock on the 8th March. There was a child with her. She asked if I sold saltpetre and how it was sold; and I replied at halfpenny per ounce. I gave her an ounce in a piece of paper. The saltpetre was rough. The size and general appearance of the prisoner is like the woman, but I could not say she is the person.

Cross-examined—Saltpetre has not a very disagreeable taste. A child might not take it of its own accord, but might be made to take it.

Jane Smith deponed—I live in Greenside Lane. I knew the prisoner’s child. It was a very healthy child. When I returned home from my work on Thursday, I heard the child was dead. I went to see the child, and asked the prisoner what was wrong. She said it turned sick when she was out with it, and vomited orange-peel.

The prisoner and Mrs Laing were in my house about three weeks before the child’s death. She came to ask me about getting employment. The prisoner said she wished to God the child was dead, as it were a great burden to her; and again she said she wished to Heaven it was dead from the bottom of her heart, for she hated it, and liked baby Hanna much better than it.[12] Mrs Laing said, “Woman, don’t say that, for I would take my bairn on my back and beg from door to door with it.” I said, “Oh, woman, you don’t know what the bairn might do for you yet.”

Cross-examined by Mr MORRISON—Witness deponed that she had had no conversation with her neighbours as to what she was to say in this case.

Mrs Laing, wife of John Laing, glazier, Upper Greenside Lane, was next examined, and corroborated the evidence given by the previous witness as to the remarks made by the prisoner with regard to her child.

Isabella Riddell or Purves deponed—I live in the same land in Greenside Lane as Innes, the tailor. I remember the day that little Willie Walker died. I went to the house that same night. I remember the prisoner coming to my house on the Friday while Mrs Jack was there. The prisoner quarrelled with Mrs Jack for saying she had given the boy poison. They were both very angry. I said that if Mrs Jack said it she was not alone, as every person said the same thing from the bottom of the lane to the top of it.

William Angus, a criminal officer, deponed—Information was sent to the Police Office on the 9th of March about the death of the prisoner’s child. I and William Smith, another officer, got instructions to proceed to the house to make inquiries. We found the child’s body in the house, and in consequence of the inquiries we made we took possession of the house.

The prisoner was there. I left Gulland and Cox, two officers, in charge of the prisoner in the house. I took possession of a pinafore and other articles of clothing. I also took possession of a small pair of boots, on the upper part of one of which I observed some small crystals. I received these articles from Mrs Innes. I kept them in my custody, and showed part of them to the prisoner at the County Buildings, when she emitted her declaration. I kept them till I delivered them up to Dr Littlejohn and Dr Maclagan. I also took possession of an empty bottle and a white powder wrapped in a paper, which were found in the prisoner’s chest in Innes’s house, and delivered them to Dr Littlejohn. The prisoner was apprehended on the Saturday.

Cross-examined—I searched her trunk and all the house. I found no saltpetre. Smith and I visited a great many shops in the neighbourhood, for the purpose of ascertaining if saltpetre had been bought by any one.

By the COURT—I know that saltpetre is an article that is commonly sold.

Dr Francis M’Cowan deponed—I am a physician residing in Elder Street. I was applied to on the 9th March to go to a house in Greenside Lane, where a child had died. It was in writing. I did not go; and in the course of the day there was a second message left at my house, I went in the afternoon to the house of Innes, the tailor, where I found the body of a male child, about three years of age. Innes and his wife were there, as also the prisoner.

I was asked to give a certificate with a view to registration of the death; but I declined to do so, as I thought a post-mortem examination was necessary. I think the prisoner took part in the conversation. She evidently wished to have the child buried, and said it could not be done without a registration certificate. When I spoke of a post-mortem examination the prisoner seemed opposed to it, but afterwards agreed to it. I declined to do it without being paid, and came away.

The prisoner called for me that same evening, and pleaded very much with me for the certificate. She said Dr Littlejohn had also declined to give her one. She was very urgent for me to grant the certificate, but I refused to do it.

The next forenoon, Dr Littlejohn asked me to accompany him to make a post-mortem examination, which l did. I made a joint report with Dr Littlejohn. Witness here read the report, which stated that their opinion was that death had been caused by the action of some irritant substance in the stomach and bowels. These and various other organs had been placed in clean jars, and delivered over to Dr Maclagan. Nitre is an irritant substance, which might produce the effects we have spoken of. I should think that half an ounce would be quite sufficient. It would produce vomiting and purging, and these symptoms would come on immediately.

Cross-examined—I cannot say I have found a great aversion on the part of the lower classes to have their friends’ bodies subjected to a post-mortem examination. Saltpetre is very often used as a medicine, and is not popularly known as a poison.[13] I am not aware of any trial having taken place of poisoning by saltpetre.

By the COURT—Dr Littlejohn and I could find nothing about the body to cause death till we opened the stomach, when there was so much appearance of an irritant substance having been used, that our impression was that death had been caused by either arsenic, mercury, or antimony. We never thought of nitre. I think it is quite possible that half an ounce of nitre might have been administered to a child in some sweet substance.

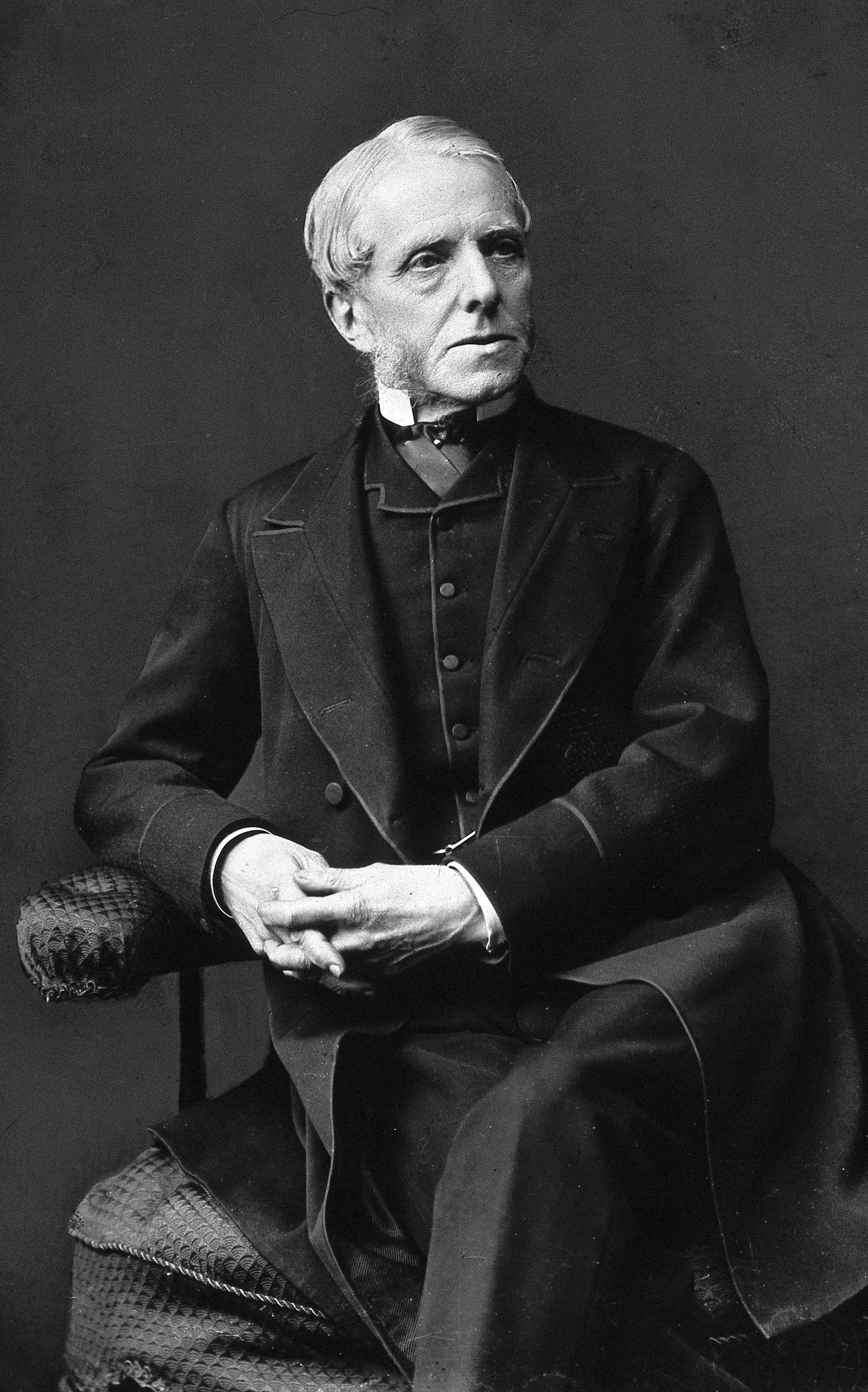

Dr Littlejohn deponed—I am surgeon of police in Edinburgh. I made a post-mortem examination of the body of William Walker along with Dr M’Cowan, and deponed to the correctness of the report read by the previous witness. Dr Maclagan and I made a chemical analysis of different parts of the body of the deceased, and also several parts of the clothing worn by the deceased. The report stated presence of nitre had been found in all the parts of the body and several of the articles of clothing subjected to analysis.

It is impossible to say what quantity of nitre might kill a child. I should think that any quantity at or above half an ounce would be certain to prove fatal to a child of that age. We obtained about ten or twelve grains of nitre as the result of our analysis, which showed that a very large quantity had been administered. The first symptoms of poisoning by nitre is internal pain in the stomach, followed by vomiting. These symptoms would show themselves in a very short time; certainly within ten minutes or a quarter of an hour. Nitre is dissolved in its own bulk in hot water, and in about four or five times its own bulk in cold water. It is my opinion that the child was poisoned by the administration of nitre.

Cross-examined—Before I went with Dr M’Cowan to make the post-mortem examination, I had a conversation with Angus, which aroused my suspicions. I think an ounce of nitre could be put into a large tablespoon as a powder.[14]

By the COURT—I think it very possible that nitre might have been administered in an orange, or as an ordinary draught. I cannot account for the presence of nitre in any other way than that it had been swallowed in large quantities. I feel perfectly confident, that in whatever way the nitre had been administered, it had been swallowed by the child.

Dr D. Maclagan deponed[15]—I am President of the College of Surgeons. There were delivered to me various productions by Drs Littlejohn and M’Cowan. I made an analysis along with Dr Littlejohn; the report shown me is a true report. We found evidence of a large quantity of nitre in the body; but I could not say how much had been swallowed. I should think that a large dose had been given. Half an ounce would be a dangerous dose to a child. It is my opinion that this child had been poisoned by nitre. The symptoms of poisoning by nitre appear very soon after, generally a few minutes. In cases of acute poisoning, death ensues in three or four hours.

By the COURT—I had no doubt that the cause of death was nitre, which had been swallowed by the child.

The prisoner’s declaration was then read, which stated that she was thirty-three years of age, and belonged to Glasgow. Deceased was her son, and was aged two years and nine months when he died; he was always wheezing at his chest, and was subject to bowel complaints.

On the 8th March she went out about two o’clock, to the Servants’ Institution,[16] and on returning to the house observed that deceased’s face was much flushed, and that spots were coming. out all over him. She took him out for a walk, and shortly after they had left the house he vomited a good deal. She offered to carry him; but he said he preferred walking; and after a short time he vomited again. She lifted him and carried him a short piece, and when he came to the house he vomited again.

She did not apprehend death was so near, or she would have gone for a doctor. About nine o’clock at night they heard him cough twice, and on going to the bed, about twenty minutes after, she at once saw that he was dead.

The declaration concluded as follows:— “I cannot account for the cause of the death. I never gave him anything that day that could have done him any harm, nor saw anything given him by another person. I gave him nothing when he was out with me, or saw any person give him anything. I took him into no shop, nor went into any shop myself. If any poison or other deleterious substance shall be found in his body, I have no idea in what manner it came there.”

This concluded the evidence for the prosecution, when Mr Morrison produced the following—

EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE.

Elizabeth Johnstone deponed—I am the matron of the Edinburgh Maternity Hospital. I have held the situation for fifteen years.

I know the prisoner. I became acquainted with her in March 1857, when she came to the Hospital with a line to be admitted. She got admittance, and was delivered of a child in about nine weeks thereafter. She conducted herself very prudently. I found her most kind and obliging, and she seemed grateful for the attention she received. She remained a fortnight after the child was born, during which time she treated her child very kindly.

A few days after she left, Dr Moir called on me, stating that he wanted a nurse for Dr Hanna.[17] I recommended the prisoner to him. I was aware that the child the prisoner had given birth to was illegitimate, but not withstanding I had the utmost confidence in recommending her to Dr Moir. She frequently visited me before she got the situation; and I always observed that she treated her child very kindly. I am aware that before she went into Dr Hanna’s service, the prisoner entrusted the child to the care of a woman. She asked me if I could recommend her to anybody who would take charge of her child and be kind to it. I gave her some addresses, but she never came back to tell me whether she had called on them.

Ann Moffat deponed—I am in the service of Dr Hanna as nurse, and have been in his house since November 1858. The prisoner held that situation before me. She came frequently to see Dr Hanna’s little daughter. The child was very fond of her. When she returned from England last she called with a present for Miss Hanna; and she brought a present of the same kind for her own child. In consequence of the kind way she treated this child, I once recommended her to a lady as nurse.

Mrs Hanna deponed—I am the wife of the Rev. Dr Hanna. I know the prisoner, Elizabeth Walker, who was in my service as wet nurse some years ago. She came to nurse my little daughter. She was with me from 8th July 1857 till 1st November 1858. I had reason to be perfectly satisfied with her while she was in my service. She was remarkably kind to the child. She called several times after she left my service, and always asked to see the child.

Rev. Dr Hanna corroborated the evidence of his wife as to the kindness displayed by the prisoner towards children. He had frequently observed that the prisoner was in the habit of speaking in an exaggerated manner, saying more than she meant. The prisoner asked him to baptise the child, which he did. He had occasion to speak to the prisoner about her child; and she showed not less than ordinary maternal interest in the child—he would say more.

This concluded the evidence, when

The Solicitor-General addressed the jury for the prosecution, and Mr Morrison for the defence.

The Lord Justice-General then summed up; and the jury after a short absence returned to Court with a verdict finding the charge not proven by a large majority.

The Court then adjourned.

Caledonian Mercury, 11 May 1860

[Images: Child top-right, Needpix.com, creative commons; Dr Henry Littlejohn, Wikipedia, creative commons.]

[4] Whitsunday was on 23.5.58.

[5] The second, older child is never mentioned by anyone again. This, added to Isabella Gould's vague sense of time and confusing way of ordering her narrative may well have added to sense of her unreliability as a witness.

[6] Elizabeth Walker later testifies that she left for the Institution at around 2.00pm.

[7] James Leith, chemist, 14 Union Pl.

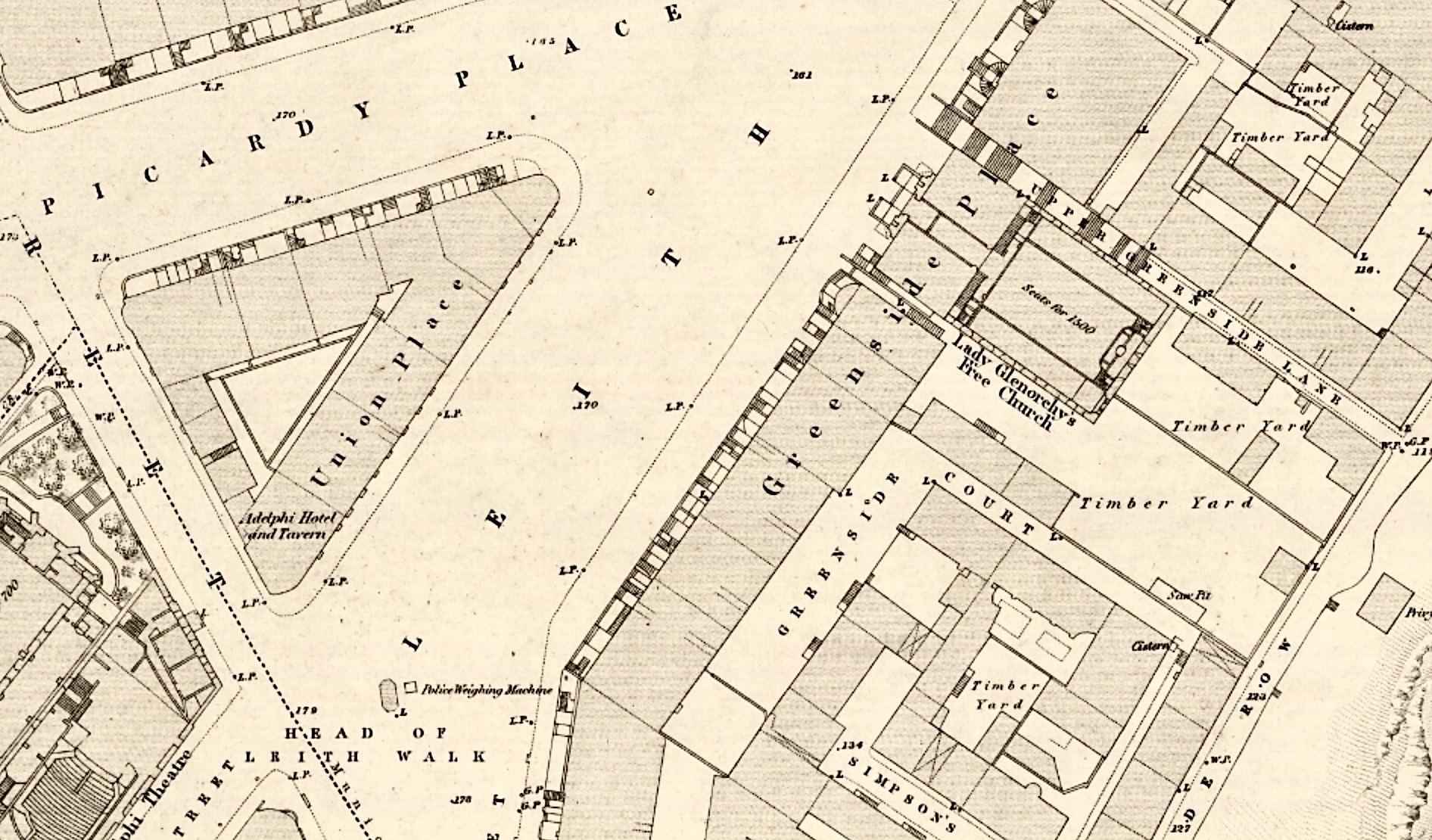

[8] Dr Henry Duncan Littlejohn (1826–1914) was Surgeon of Police and Medical Officer of Health of Edinburgh from 1862 to 1908. He was later to be a model for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, and Conan Doyle was born around the corner from these events (on Picardy Place) in May 1859. M’Cowan, doctor of medicine and surgeon, resided at 23 Elder St.

[9] Grocer and wine merchant, resident at 16 Hart Street, business at 11 Union Pl.

[10] Saltpetre (potassium nitrate) was commonly used for curing and preserving meat.

[11] Provision merchant, 2 Union Pl.

[12] Elizabeth had served as a wetnurse to the daughter of the Rev. Dr Hanna in 1857, shortly after the birth of her own child William. See n. 13.

[13] It has been used for the treatment of asthma and high blood pressure.

[14] William Angus was the police officer who gave evidence a little earlier.

[15] Dr Douglas Maclagan, M.D., F.R.C.S. and lecturer on materia medica, 28 Heriot Row.

[16] 4 South Charlotte St.

[17] Rev. Dr Hanna, residing at 6 Castle Ter.