GAYFIELD SQUARE

From East London Street, a setted prelude sweeps south through the ghost of the Estate. I meander up past whitewashed creation. Opposite, beyond finialled railings and letterbox fanlights, attic windows extrude like pop-up flashes.

Thrawn at the apex by black cat glare: a sunny sinecure interrupted. A creature of the New Town steppes, viridescent eyes containing complex knowledge of adjacent nature.

A lone police van detaches from the Sixties station and circumnavigates the square, a bloodless beast scanning its territory. Semper vigilio. In its animal wake, I cross over, through a municipal threshold, and into green.

Adjourning to a weathered bench backdropped by B-list villas, I look towards the ashlar casts of east-side tenements. Under the sombre sky, a grande dame floats through early afternoon with all the austere refinement of la veuve herself. A rare treat.

No memorials here denote late locals' favourite spots. The garden has little truck with human past: its demesne is timeless nature. Anthropoids are welcome, but not privileged.

Counselled by the noontide sun, the square extends a dendritic hand towards Haddington Place. The gesture injects a degree of urban effervescence, but doesn't overwhelm. There is détente here: nature at ease with the city.

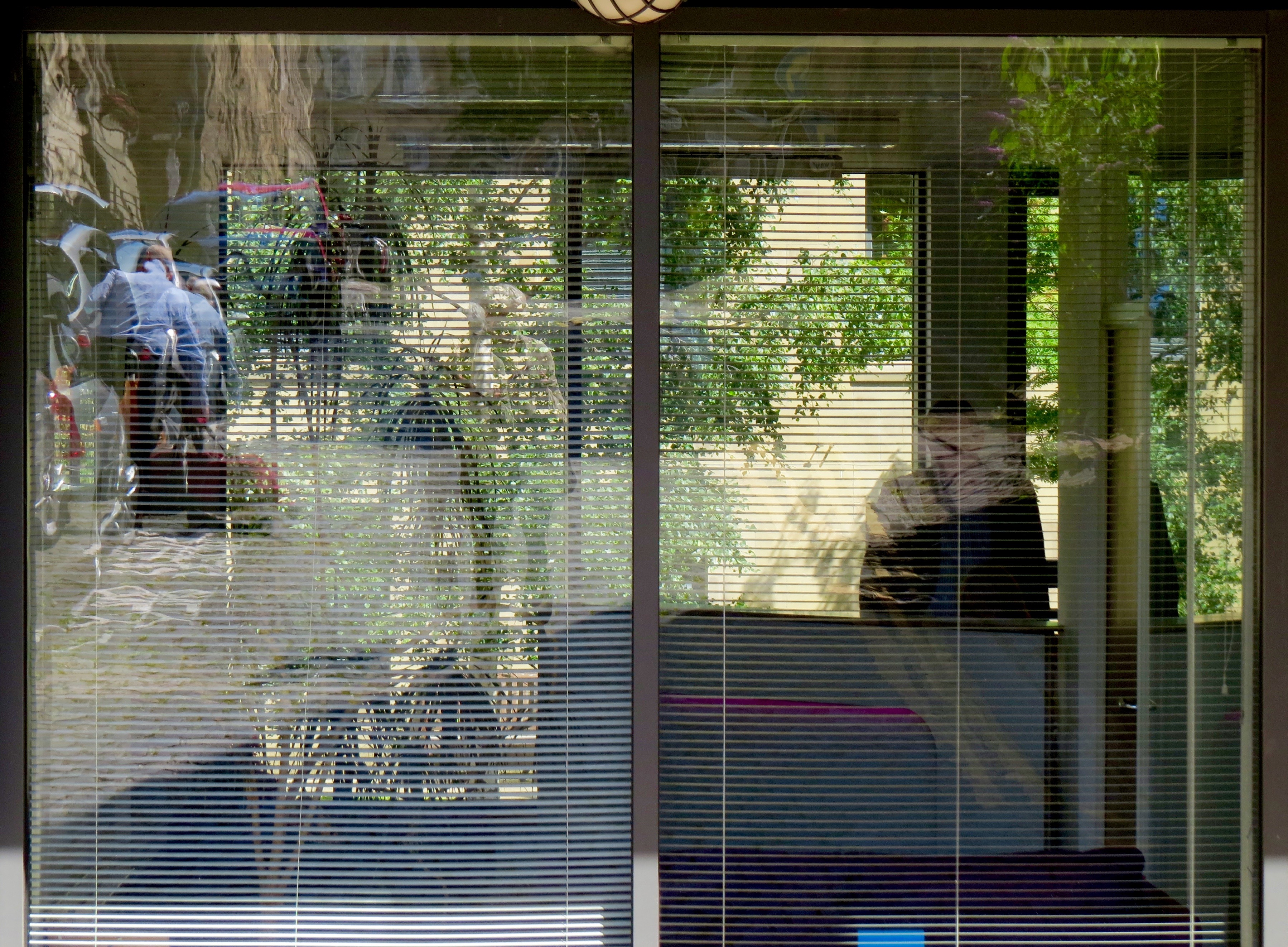

In an unseasonably cool breeze, I recall the garden's chill winter overcoat, and being gripped by the molten glare of sashes deranged by a viscous sun. How I miss the urgent, ephemeral refulgence of winter's quickening.

Enough of this reverie!

I adjourn to a western tributary and find modest, time-worn tenements fronting modern buy-to-lets. These new builds belong anywhere and serve as monuments to nothing.

Perhaps my feline collocutor, now nowhere to be seen, instinctively grasps what I too have come to know: that Gayfield Square possesses a dual identity.

It is incurably Georgian and indisputably Other.

This otherness, its 'character', is only superficially a function of archidiversity. The profound distinction here is spatial. Openness conveys a welcome that, for the New Town at least, is unusual.

Contrast this with the hostile intentions of other New Town gardens: designed to repel, to encourage you to move on. There is nature there, but perhaps not for you.

Gayfield Square is an expression of a different modus vivendi, a product of a different philosophy of the city. It has grown up with the urbe rather than struggled against it.

It should be treasured.

Much more than urban space, it is urbane.—David Hill