DAVID HILL ON RODNEY AND BROUGHTON STREET HAUNTS – THE GHOSTLY AND THE GHASTLY

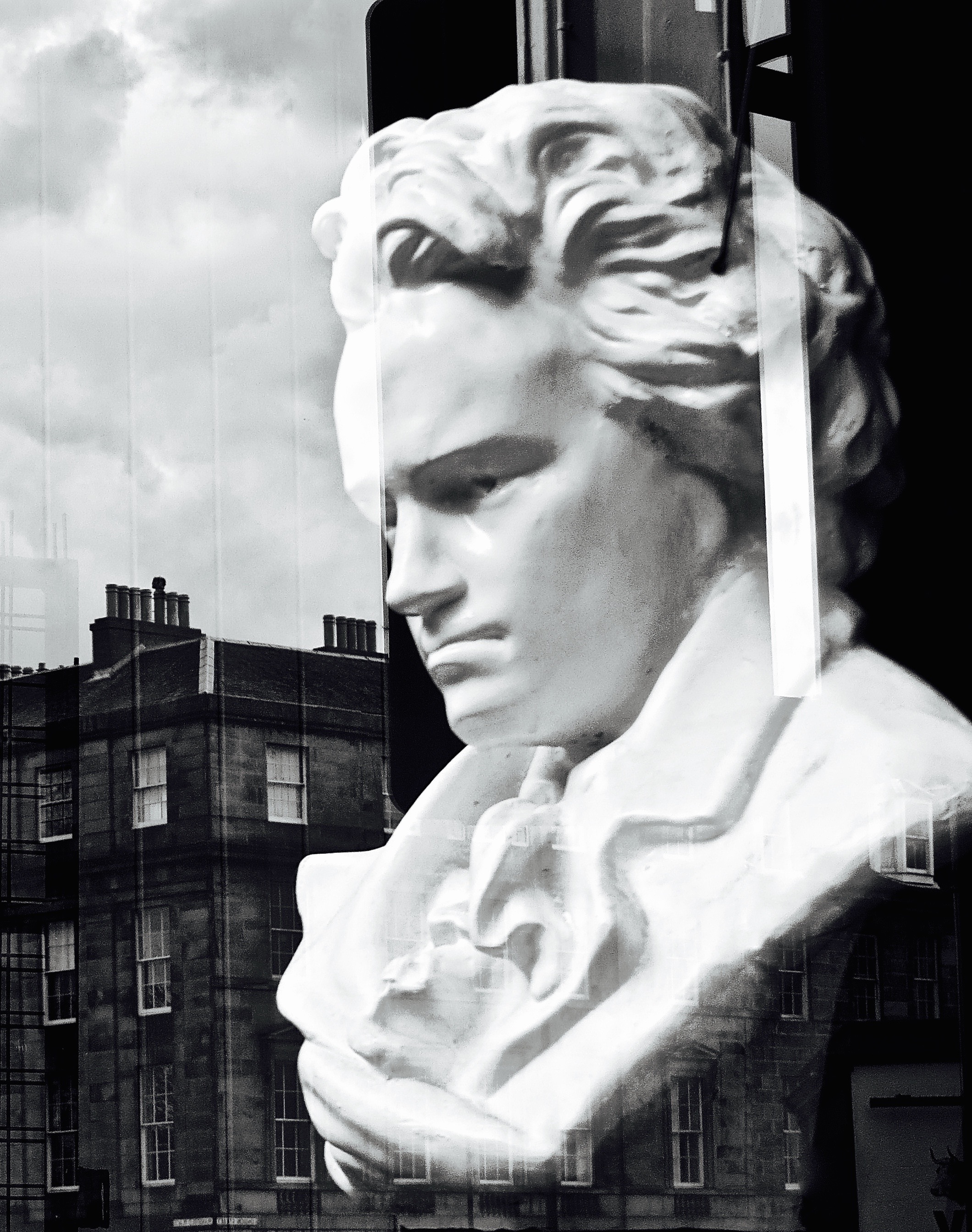

Ghost signs – hand-painted traces of an earlier generation's entrepreneurial spirit – are a well-documented and much photographed phenomenon.

Like abandoned departure boards displaying destinations no longer served, these faint contours of past commerce make promises that cannot now be fulfilled.

Nonetheless, they assert their spectral presence in contemporary urban landscapes by adding texture and, sometimes, expressionist harmony. It is something of a paradox that the accidental phantom sign often fits organically into the present while the deliberately preserved one can feel awkward and misjudged.

The close-to 120-year-old painted sign above the street's fishmonger is both mirror to the past and contemporary reboot. Confident and comfortable among brightly polychromatic neighbours, it has, for the past few years, provided a tangible link to the late 19th century.

If the ghost sign offers a physical connection to Rodney Street’s relatively distant past, an ethereal counterpart to its more recently deceased can be found online in Google Streetview.

The map, Google or otherwise, may not be the territory, but technology permits a fascinating stroll down memory byte lane. The application’s Edinburgh presence matches my own, give or take a few months. For me, glimpses of earlier streetscapes function as more than mnemonic: they're picture books narrating personal stories of the city.

Its buildings, however, are not my main concern.

Like me, you may find that on Rodney Street, the only scape you have in mind is ... escape. Pedestrians beware: here, the doctrine of shock and awe is still employed with abundant enthusiasm

For those on foot, it’s overwhelming and spectacular.

The quantity and volume of traffic on Rodney Street engenders an ambience not so much ghostly as ghastly. As all too often in Edinburgh, being a pedestrian entails abundant psychic pain.

Unfortunately, the distant Valhalla proves, on closer inspection, to be chimera.

This is a capricious street, of people one minute contentedly sipping their Flat Whites, the next enduring motor mayhem. No one lurks outside here except for reason of nicotine. Continuing the Rodney Street theme, this street’s al fresco, too, is mostly characterised by grim determination in the face of overwhelming traffic-induced misery.

Broughton Street, allegedly numbering among the city's most urbane thoroughfares, is, in reality, a Neanderthal in a trendy suit.

We're not talking about a mortal sin here, just the all too normal motor one.

Up where the street meets Picardy Place, we, all too briefly, experience something else. Here, Paolozzi's Manuscript of Monte Cassino sits patiently, receiving the occasional pilgrim. The sculpture, and the space it possesses, provides a moving coda – and contrast – to the rest of the street's fortissimo.

In drawing our attention to slow time and longue durée, the work emphasises a different pace of life. In doing so, it, unintentionally, draws attention to a different philosophy of the street; one in which people enjoy places and spaces in themselves, and see them as means to communal as well as commercial ends.

As for the rest of Broughton Street, the only phantom presence, as far as I can see, is the yoked and humbled pedestrian.

But who believes in ghosts?

---------------------------

A controversial but lyrical paean to Broughton Street. New Town flaneur wannabe @eyebrowsofpower take note...