'THE HEAVY OF YOUR BODY PARTS AND THE COOL AIR OF THE AIR CONDITION' — REVIEW

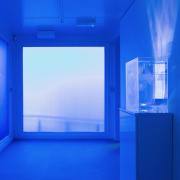

Before viewing Glasgow-based artist Ross Little’s film, one passes a tank in which jellyfish drift on invisible currents, illuminated in blue and pink.

These composite creatures, these ‘living transparencies’ travel the world without conscious direction, insubstantial, seaborne, vulnerable, venomous.

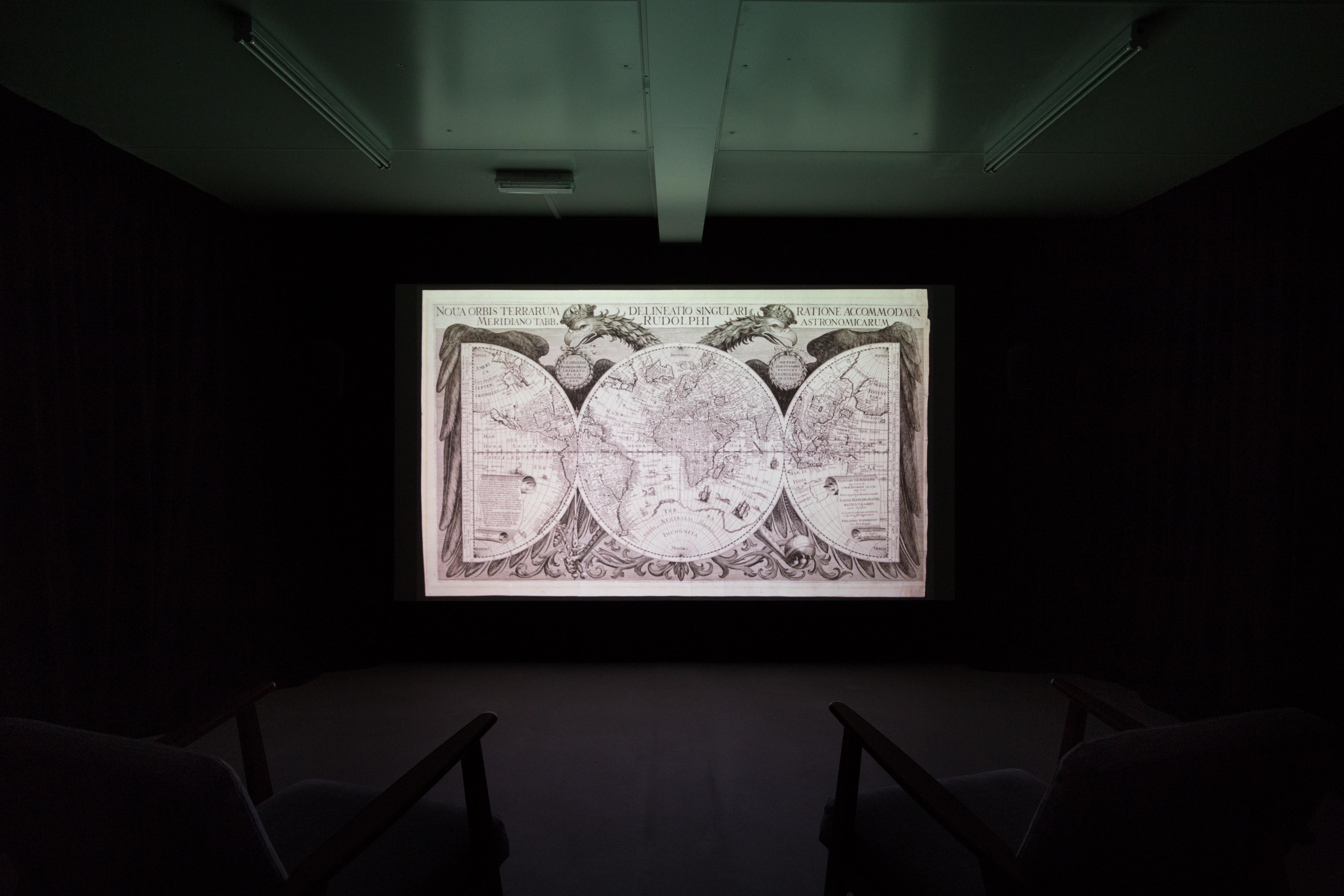

For Little, they represent at different levels the motivations, beauties and contradictions of life in today’s globalised world – themes picked up in the (looped) 42-minute film’s opening sequence showing antique maps.

We soon find ourselves amid the rather tawdry glamour of a cruise ship leaving port. Little films in long, uninterrupted shots, moving amid passengers and crew. He provides nothing in the way of editorial comment, but allows the voices and clatter of shipboard voices and performance to speak for him.

He is quietly damning and slyly funny. The décor is designed to dazzle, but the failing lights flicker distractingly overhead. Individuals are herded into group activities and mind-sets, lulled by lift music, controlled by cabaret congas, timetables for eating, dancing, swimming by numbers. Crewmembers hurry between tables carrying food and drink. They are contractually obliged not to interact with passengers beyond the strict requirements of their duties.

Conversation wanders between relaxation hypnosis and the prevalence of offshore tax havens. One interviewee describes his floating, rootless existence as a ‘digital nomad’ who perpetually cruises whilst running an unseen business operating thousands of miles away. ‘I chose freedom,’ he says, perhaps unaware of Dr Johnson’s maxim, ‘[B]eing in a ship is like being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned.’

All aboard and around the ‘Nomad Cruise’ are in some sense prisoners – prisoners within the confines of the vessel, prisoners of class and capitalism, prisoners of inhumane value systems.

From ersatz luxury to decomposition. Little travels to the shipbreaking yards of Alang in India. Here, ships come to die. Workers without adequate physical protection or financial reward toil at dismembering the carcasses. The sea is stained red with rust.

In conclusion, there follows an extended visual poem filmed in a scrapyard to the ambient soundscape of snatched conversations, car horns and two-stroke moped motors. It is a study in bizarre repetitions, decontextualised objects, familiar forms rendered unfamiliar and disconcerting. It is the world dismantled, a world of …

anchors and boiler tanks, coiled hosepipes and chains, helmets, lights and computer printers, screens, safes, radios, photocopiers and TVs, video players, hifis, washing machines, weights and exercise equipment, bar stools, piled mattresses, landscape paintings, model animals – a rhino, hippo, zebra, giraffe and tyrannosaurus rex, swans, dolphins – things that cannot be identified and things that have no name, mops, brushes, poles, scrubbing brushes, plungers, wipers, masks, clocks, boxes, scales, spindles, marker pens and bulldog clips, lampshades, anchors and boiler tanks, coiled hosepipes and chains and so on and on and on …

None of it makes sense. It all makes sense. It is a world of flotsam and jetsam, the end of creation, a primal soup. It’s absolutely fascinating, and a lot more visually beguiling than the stills shown here suggest. I can’t recommend it highly enough.—AM

Ross Little’s The Heavy of Your Body Parts and The Cool Air of the Air Condition continues at Collective Gallery on Calton Hill until 10 September. Entry free.

[Image Credits. Top-right: 'I Hear a New World Calling Me, jellyfish, 2017. Photo by Tom Nolan. All other images: 'Ross Little, 'The Heavy of Your Body Parts and the Cool Air of the Air Condition', HD video, 42 minutes and 24 seconds, looped, 2017. Photo by Tom Nolan.]