ODD GOINGS-ON IN HEART OF THE NEW TOWN

This Edinburgh property may be found at 19 York Place.

It’s perfectly pleasant, as you can see, and would probably never have drawn anyone’s attention to itself today had it not figured as the backdrop to a rather peculiar tale of supernatural visitation.

Back in 1844, No. 19 was the home of the most distinguished consulting physician of his day: Dr John Abercrombie.

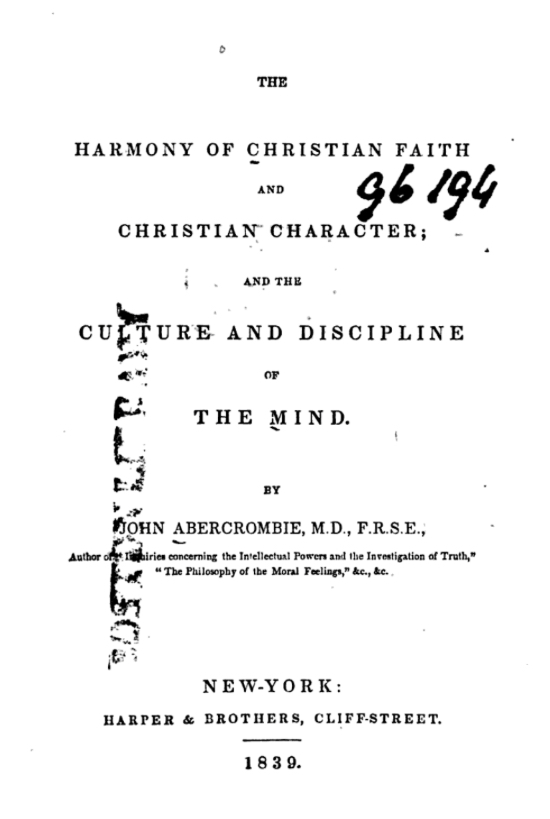

Abercrombie (born in 1780, and practising in Edinburgh from 1803) was well known for his Pathological and Practical Researches on the Diseases of the Brain and Spinal Cord and Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers, containing many entertaining anecdotes about mental disorder, assembled during his extensive professional career. Towards the end of his life, he also came to expound upon Moral Philosophy.

It was while preparing to set out on his rounds one morning at 11 o’clock that Abercrombie died suddenly at home of a burst coronary artery.

The historian James Grant (Old and New Edinburgh, vol. 3), now picks up the story nearly half a century later:

A Mrs. M., a native of the West Indies, was at Blair Logie at the time of the demise of Dr. Abercrombie, with whom she had been very intimate. He died suddenly, without any previous indisposition, just as he was about to enter his carriage in York Place … on a Thursday morning.

On the night between Thursday and Friday, Mrs. M. dreamt that she saw the whole family of Dr. Abercrombie dressed entirely in white, dancing a solemn funeral dance, upon which she awoke, wondering that she should have dreamt anything so absurd, as it was contrary to their custom to dance on any occasion.

Immediately afterwards her maid came to tell her that she had seen Dr. Abercrombie reclining against a wall ‘with his jaw fallen, and a livid countenance, mournfully shaking his head as he looked at her.’

She passed the day in great uneasiness, and wrote to inquire for the Doctor, relating what had happened, and expressing her conviction that he was dead, and her letter was seen by several persons in Edinburgh on the day of its arrival.

Abercrombie had in fact recovered from an attack of paralysis earlier in the year, but Grant does not allow this to get in the way of a good story. Annoyingly, he fails also to source the account of the doctor’s strange appparition, a forensic shortcoming which would have appalled the meticulous Abercrombie almost as much as Mrs M’s departure from the tenets of theological conformity that had punctuated his non-scientific writings nearly to the end.

Not getting the last word has long been one of the major disadvantages of death.

For those who take an interest in these things, an online dictionary of medical eponyms notes that, during a post mortem examination, Abercrombie’s ‘conspicuously large brain’ was found to weigh 46 oz.