THE STOCKBRIDGE MURDER CASE, 1889

Part II

––––––––––––––

KEAN’S CAREER.

Her Early Life.

There seems good ground for supposing that King or Kean, for the latter is the woman’s correct name,[1] has been guilty of more than the two murders for which she has been executed, and she seems to have shifted from one part of the city to another and to have the children under different names in order not to attract suspicion.

The murderess was born at Blackshand, Kelvinhaugh, in the Anderston district of Glasgow, on 27th March 1861.[2] She would thus have seen her 28th birthday had she lived to 27th inst. Her father was a cloth yarn warper, and the family consisted of two brothers, Peter and John, and the subject of the present sketch. The mother died when Jessie was only 18 months old, and the father died in June, 1879, when she was 18.

Three years after his death she went to Bonhill, Alexandria, and worked in the mills at Renton. Her career here seems not to have been of the best, for we find her next in the Magdalene Asylum, a home for fallen women, of which institution she was an inmate for 18 months. Here she learned laundry work, by which she eventually was able to earn a good livelihood when she liked.

Her next move was to lodgings in the South-side of Glasgow, where she stayed two years and then went to Gourock, working in a laundry there for a year or so. While in Glasgow it is rumoured that she underwent three or four months’ imprisonment for […]

[1] The paper’s switch from King to Kean was probably no coincidence. In the sensitised anti-immigrant climate of the period, the Kean surname would likely have ‘dog-whistled’ the Irish and Roman Catholic origins of the convicted criminal’s family. As DM observes, ‘The Irish in Scotland and England were considered to be a different race with a different religion, and “To their great indignation, [they] tended to be lumped together as ignorant, dirty and primitive Paddies or Biddies” (Swift 1987: 264).’ [Swift, R. (1987), ‘The Outcast Irish in the British Victorian City: Problems and Perspectives’, Historical Studies 25 (99): 264–76.]

[2] SR Births 644/8 361 gives the address as Black’s Land. She was the daughter of James Kean, cotton yarn warper, and Grace Giddell, who had married on 31 August 1854 in Glasgow.

Concealment of Pregnancy.[3]

From Gourock Kean came to Edinburgh, and found employment in a laundry in the Causewayside district as an ironer. In that capacity she earned capital wages, being reported to be a smart and capable worker. Her fellow workers considered her cold and reserved disposition as the only striking feature of her character, and general surprise was expressed on the news of her foul deeds becoming known.

During her engagement at the establishment in question, she obtained lodgings at a house in Gifford Park, occupied by Thomas Pearson, whose acquaintance she thus formed. At this time Pearson cohabited with a woman, whose name is supposed to have been Taylor, and the latter becoming jealous of the attentions paid by Person to Kean made matters so uncomfortable for all parties that the interloper sought lodging elsewhere.

Obtaining shelter with an elderly couple in Sciennes, Kean remained with them for 16 months, to May 1887, during which time her behaviour afforded little ground for complaint. Here she was frequently visited by Pearson who was represented as her uncle and their intimacy resulted in Kean being delivered of a female child at the Maternity Hospital on the 25th May 1887.

[3] This crime included not seeking proper advice before or help during birth, and not registering the child afterwards. Jessie Kean worked as a laundress in Duncan Street around 1881, according to K. Winton, Murder in Edinburgh (1985).

One Murderess Succeeds Another.

After leaving the Hospital, where Kean stated Glasgow as her birthplace, she again cohabited with Pearson, the couple occupying his house at Gifford Park, the woman Taylor having sometime before died in the Royal lnfirmary.

Taylor, it may be mentioned, was known by South Side laundresses, among whom she bore an evil reputation. Twenty years ago, it is said, she was a domestic servant with a well-to-do family residing in the Grange district. The discovery of a dead child concealed in a coal bin was, it is stated, followed by her arrest and trial on a charge of child murder.[4] Released after undergoing 15 of a term of 20 years’ penal servitude, she obtained employment at a laundry, which she left to keep house for Pearson while residing at Gifford Park.

Pearson and Kean attracted little attention, their only claim to notoriety being Pearson’s pipe-playing accomplishments, which earned for him the soubriquet of “the piper.”

[Gifford Park image: DM.]

[4] One Ann Taylor was tried for concealment of pregnancy and child murder on 15 Feb. 1858. On 5 Jan., in the Glenfinlas St house (Edinburgh) of Mr T. Graham W.S., she had used a razor or similar sharp instrument to cut her daughter’s throat shortly after birth. She pled guilty to culpable homicide and was sentenced to 10 years’ penal servitude (see CM, 16.2.1858). Ann Taylor, domestic servant, single, died of mouth cancer in Edinburgh’s New Royal Infirmary on 9.10.1883, aged 45. Her normal residence was listed as Forfar (SR Deaths 685/1 994).

A Mysterious Disappearance.

The birth of the child, which was named Grace, was duly registered, and about four months later intimation was given of the fact that it had been vaccinated.[5] Since that date—September, 1867—so far as can be ascertained, all trace of the child has gone, its whereabouts, so far as her former neighbours and acquaintances are concerned, consisting a mystery.

To several parties Kean gave out that the child had died in infancy though she refused to state its burial place, while others were informed that it had been adopted by a lady. On another occasion she told a female friend that the child had died suddenly and that she was going to take it to a medical man to have it examined. Struck by the strangeness of her talk and demeanour the person confided in remonstrated with her but hearing nothing further of the child the matter was soon forgotten, till, on Kean’s arrest, the worst suspicions of her acquaintance were aroused.

[5] Grace King was born in the Royal Maternity Hospital on 25 May 1887, and appears to have been named after her grandmother (although King replaced Kean as the surname). The address of her mother was given as 21 Gifford Park, but the father was not named (SR Births 685/4 585).

The Second Murder.

On leaving the Maternity Hospital, Kean had removed to the house, 24 Dalkeith Road, which Pearson and her tenanted from May to November, 1887.

She was then seen with a strange child in her possession, which was variously represented as the surviving child of her “brother the clergyman,’’ as the son of a neighbour, and as an adopted child. This baby was Walter Anderson Campbell, son of Elizabeth Campbell, a Prestonpans wire worker, who died soon after its birth. Pearson and Kean gave the name of Stewart when negotiating for the possession of this child, and the convict was paid £5 to adopt it.[6]

The child was allowed to live from two to three months, but in the beginning of November, it suddenly disappeared, the story being that it was sent home to its aunt and again to its father. The charge of murdering this child was preferred against Kean at the trial, but ultimately withdrawn on the ground of insufficient evidence. It was thought that child had been buried under the flooring of the house, and, indeed, it is rumoured that Kean confessed as much, but a search revealed no trace of anything of the kind.

[Dalkeith Rd photo: DM.]

[6] About £410 today, or 15 days’ wages for a skilled tradesman in 1888.

Third Child Disappears.

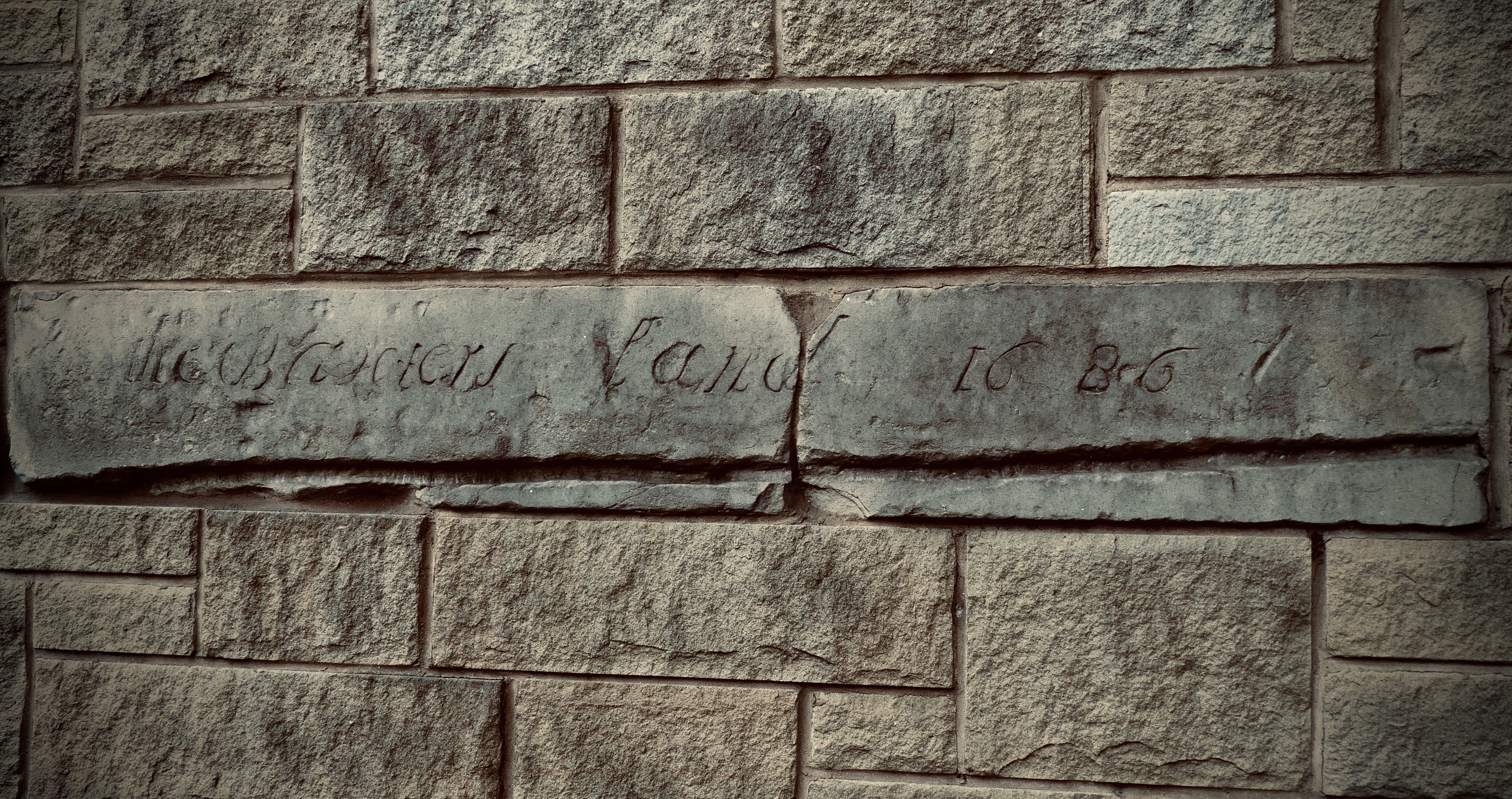

From Dalkeith Road Kean went to stay at Baker’s Land, Canonmills, and subsequently to Ann’s Court,[7] in the same district—both well removed from the scene of former operations.

When in Ann’s Court she got a child named Alexander Gunn, on 4th April last year, to adopt, receiving £2 with it. By this time the couple had taken the names of Mr and Mrs Macpherson,[8] and the child Gunn was given out as the son of Macpherson’s brother. It was kept till the end of May, and here we are indebted to the culprit’s own statement as to what followed.

In her confession Kean said that one night when Pearson was out she strangled the child. She did this because she had no other means of supporting it. After it was dead she wrapped it in a cloak, and placed it in a box, where it remained till next day, when she took it out and placed it in a cupboard. It lay there for about three days, when they removed from Canonmills to Stockbridge.

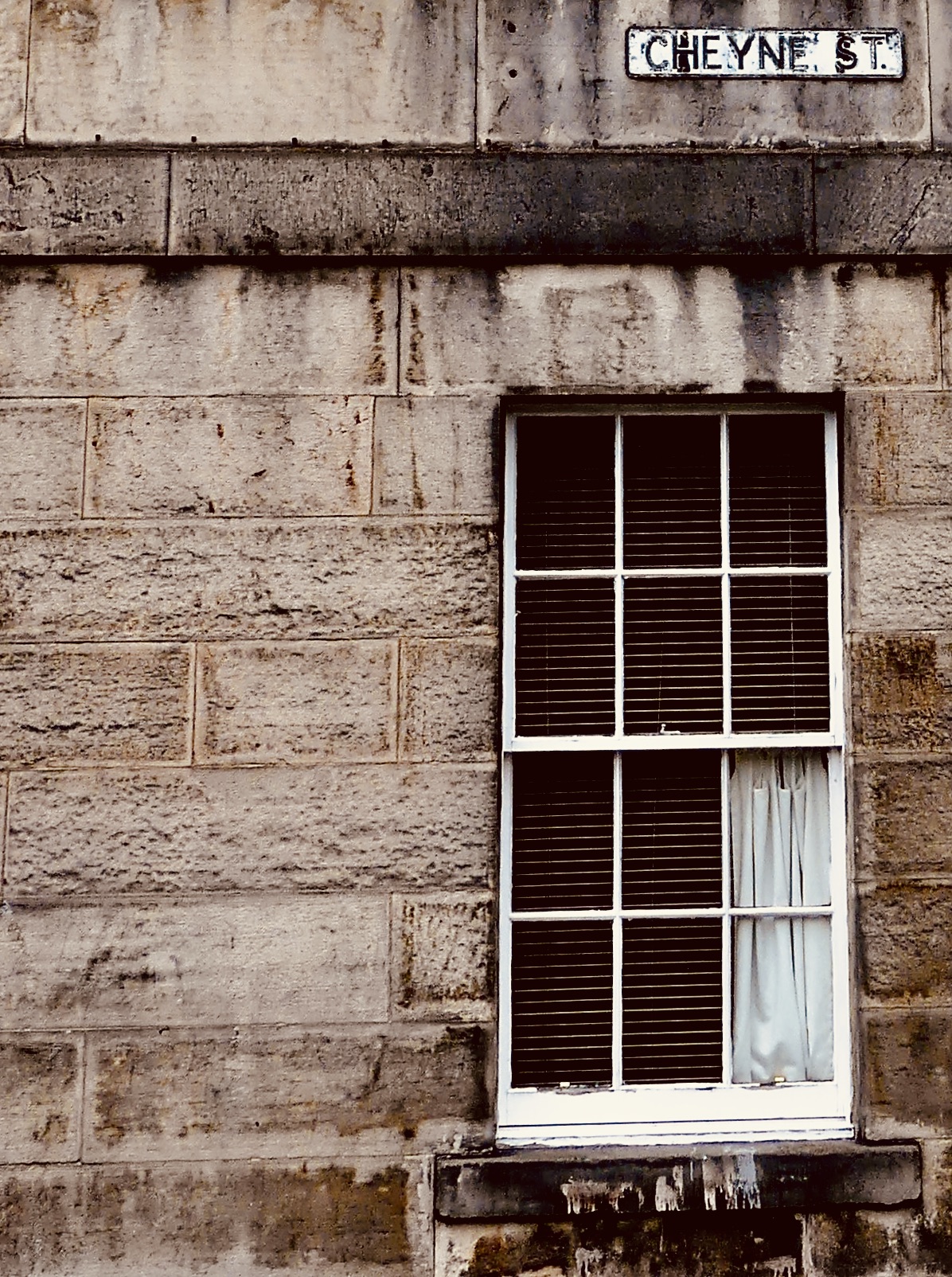

She placed the body in a closet or cellar at Stockbridge, where it remained until about a fortnight before it was found. She took Pearson’s waterproof coat to wrap the body in, in order to keep the smell from coming out, and eventually placed the body in a piece of ground at Cheyne Street. Kean further stated in her declaration that she deceived Pearson as to the child by telling him that she had put it into Miss Stirling’s Home in Stockbridge. The finding of the body of this child was the means of discovering the culprit, and also led to the exposure of […]

[Baxter's Land photo: DM.]

[7] Ann's Court and Baker's (Baxter's) Land have now been replaced by the BP petrol station at 23 Canonmills. An old lintel inscription from the latter has been preserved.

[8] Pearson is an anglicised version of Macpherson. The frequent changing and disguising of names and relationships suggests that both parties in the relationship had something to hide. See Note 1 here.

The Fourth Murder.

Kean entered into possession of the Cheyne Street house in June last year, and in the September following she got another child to adopt, this time giving her name as Mrs Banks—that of the person from whom Pearson and her had rented a room.

The child was named Violet Duncan Tomlinson, daughter of a domestic servant, and was six weeks old. Kean got £2 with it, and, according to her own story, as soon as she took the child home she gave it whisky to keep it quiet. The liquor, she said. was stronger than she thought, taking away the child’s breath, and while it lay gasping she put her hand to its throat and choked it. She then put the body into a cellar, and it was found there.

In October the convict went to the Maternity Hospital and was delivered of a child, which she has since named Thomas Kean.[9]

[Cheyne St photo: DM.]

[9] Thomas Pearson King was born at the Royal Maternity Hospital on 14 October 1888. Jessie did not name the father, and her son was described as ‘illegitimate’. Her address was 2 Cheyne Street, and she described herself as a laundress (SR Births 685/4 1062). The house at No. 2 no longer exists.

A Fifth Murder Suspected.

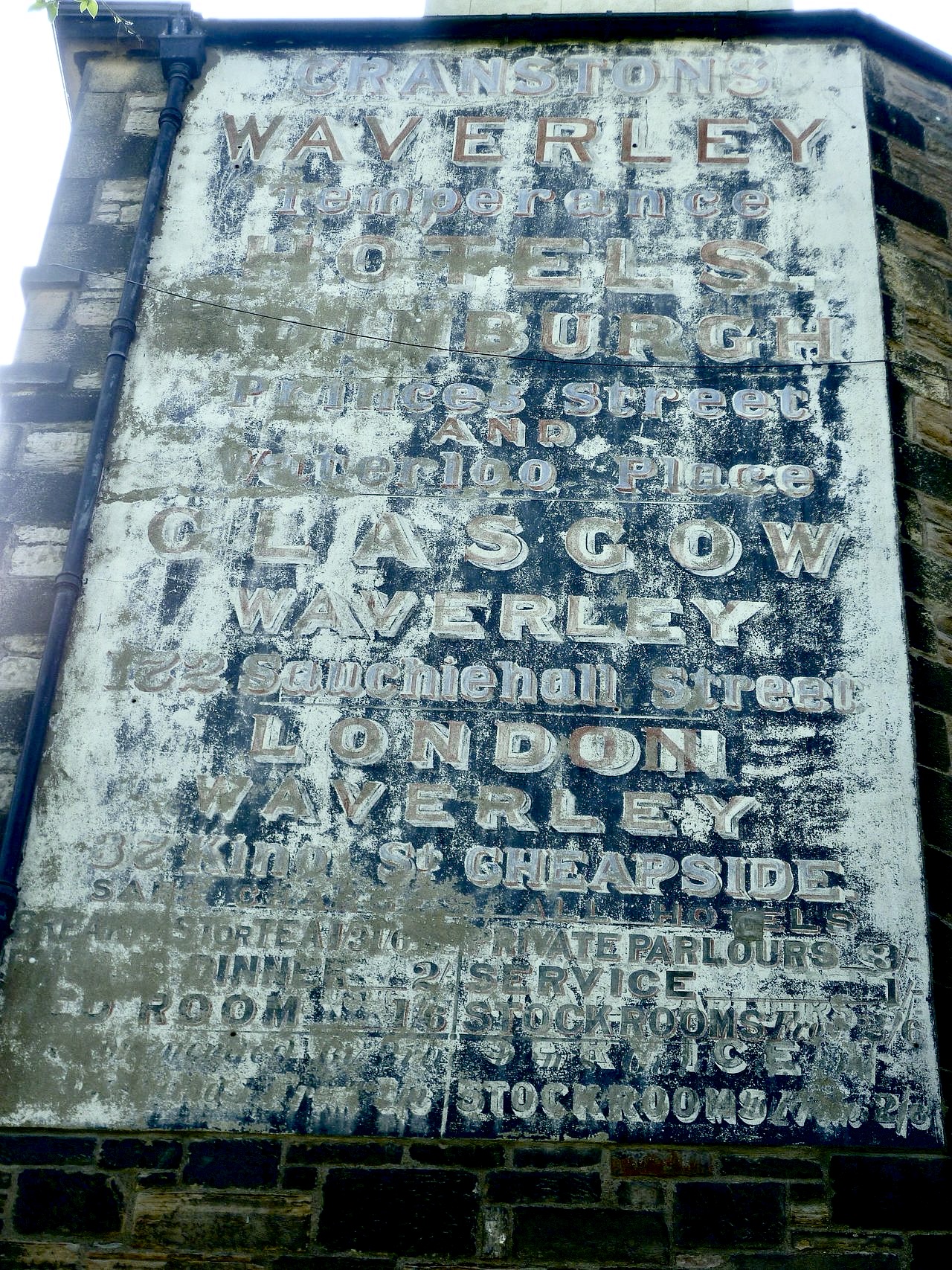

Though evidence to substantiate a fifth charge of murder could not be found, it is believed that Kean was the person who put a child in a bonnet box and left it at Abbeyhill Station last summer.[10] She was seen while at Baker’s Land to have in her possession a bonnet-box with a dint in the side, and this she had as long as she was in the house in question.

After Kean’s apprehension some of the neighbours were taken to the police office, and stated that the box in which the Abbeyhill child was found was exactly like the one Kean had, but further testimony could not be had, and no charge was preferred.

[Photo of Cranston Temperance Hotel advertisement above Abbeyhill Station platform: Wikipedia, Creative Commons.]

[10] On 26 Sept. 1888, the Scotsman reported the discovery, in a tin hat box deposited at Waverley Station’s Left Property Office, of a new-born boy’s body. It had been there for 2 weeks and was thought to have arrived on a suburban train. The same report mentioned another child’s body found in a box, ‘not very long ago’, under the seat of a first-class carriage of a Leith train at Abbeyhill.

How the Crime Came to Light.

The discovery of the crimes was partly due to the woman’s own recklessness.

The very day after she had placed the body of the little boy Gunn in the back green of the house in Cheyne Street, it was discovered by some boys who were playing, and who at first used what they thought to be a bundle of old rags as a football. To their horror, they soon discovered that it was the body a dead child.

The discovery was published in the Evening News of October 27 and various rumours were quickly current in the district as to the perpetrator of the deed. Mr and Mrs Banks became suspicious of their lodgers, owing to their coal closet being kept locked, and informed the police. Detectives James Clark and David Simpson were entrusted with the work of discovery, and on entering Kean’s house they found the body of the child Tomlinson lying on a shelf in the cupboard. A piece of black cloth similar to that found round the body of the other child, was discovered in the closet.

Kean at the time confessed to the murder, and on being taken to the police office she renewed her confession there. This destroys entirely the objections which have been urged against the formal confession in the prison. In the case of the children Gunn and Tomlinson, death had been caused by strangulation, the woman having tied a cord twice round the neck, knotting it firmly under the left ear.

Edinburgh Evening News, 11 March 1889

[Photo: Fire and Police Stations, Hamilton Place, 1890. Edinburgh & Scottish Collection, Item 14851.]