THE STOCKBRIDGE MURDER CASE

1889

Part IV

THE EXECUTION.

––––––––––––––

Within the prison walls the bright morning made things look quite cheerful. The ordinary decorum was not much interfered with, the officials moving about with probably a little more solemnity than usual. The magistrates—Bailies Russell and Steel—with their officers; Dr Littlejohn and his son,[1] Mr Henderson, the chief constable Mr Morham, Dr Hay, the prison doctor; the Rev. Mr Fleming, the prison chaplain; as well as the privileged few who possessed warrants admitting them to the ceremony, began to arrive about half-past seven.

When all were admitted they were conducted in a body by a circuitous route, through long corridors to the matron’s office, a dingy little apartment, where they waited while the final arrangements were being made for the execution. The tolling of the prison bell began then to fall on the ear, not loud.

A more ominous spectacle was shortly observed in the corridor, when Berry appeared with the pinioning apparatus in his hand.[2]

[…]

TO THE SCAFFOLD: TOUCHING SCENE.

The executioner entered the condemned woman’s cell almost simultaneously with the civic authorities, the latter of whom Kean received with a composure which the magistrates and all who were present declare to be wonderful.[3] She was standing near the priest, the Rev. Canon Donlevy, who at once proceeded to read the Litany.

Just before this, however, a painful scene occurred. Round the door of the condemned cell was gathered a group of weeping female warders. The scene was touching. The condemned woman advancing a pace before joining the procession, which was now in course of formation, shook hands with each of the warders, muttering to them individually, ‘The Lord be with you.” The solemnity of the scene was rendered more impressive by the calmness of the woman’s demeanour and the subdued expression on her face.[4]

Leaving those who tended her during her incarceration and to whom she seemed much attached, she joined Canon Donlevy, and to him she communicated a message to convey her heartfelt thanks to Dr Hay, the junior surgeon. Addressing the Canon, she with a faltering voice thanked him in the most cordial manner, saying “May God Almightly bless you all.”

Then she was pinioned, submitting to the process with the same composure. A white cap was drawn over her face. The procession was by this time formed, and she expressed her readiness to proceed.

A movement was then commenced in the following order: City officers, with halberds, two abreast; Magistrates, Bailies Russell and Steel, carrying white rods; governor of the prison, the surgeon of the prison (Dr Hay), accompanied by Dr Littlejohn and Dr Harry Littlejohn; Canon Donlevy, in white surplice, with the condemned woman leaning gently on his arm, and in the rear a body of warders.

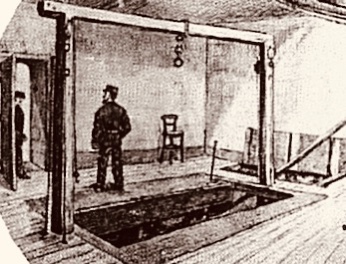

The scaffold was erected in an apartment next door to the condemned cell, and consequently the walk was not more than a dozen yards. Immediately on the walk being commenced, Canon Donlevy began in solemn tones to read the “Litany of the Holy name of Jesus.” Kean answered quite distinctly the responses, “Lord have mercy on my soul.”

ON THE SCAFFOLD.

A minute had scarcely elapsed from the time she quitted her cell till the unfortunate wretch was standing on the drop below the noose. A second was sufficient for Berry to bind her legs and then the noose was adjusted round her neck with similar alacrity. Not till then did she cease repeating the responses.

Her last words, which were only indistinctly heard, were: “Unto thy hand, O Lord, I commend my spirit. Lord Jesus, receive my soul. Jesus, son of David, have mercy on me.” As these last words were uttered, the executioner drew the bolt, and, with a deep thud, the convict dropped into the pit beneath.[5]

Berry stood on the left side of the scaffold, and looked after his victim with a sympathetic eye. His first remark as he gazed on the lifeless body was that neither the rope nor the body had quivered a bit. The body hung quite still. The head was thrown over upon the right shoulder, exposing the neck, upon which there was a slight discoloration. The only other part of the skin visible was the hands. These were quite livid in appearance, half-closed, and in them she grasped a small black cross.

About five minutes after the execution Berry descended into the pit, undid and removed the leather belt with which the feet were secured, and took from her hand the cross, which he handed over to the governor of the prison. A little later on he removed the cap from the face, and thereafter the cell was cleared of everyone and the door locked till nine o’clock, when the body was taken down and placed in a plain black coffin.

Edinburgh Evening News, 11 March 1889

[1] Dr Littlejohn (snr) first appeared in these pages some 30 years earlier, in a case of alleged infanticide (News from the Mews 12, Note 8). Littlejohn’s son, Dr Henry Harvey Littlejohn (1862–1927), became Chief Police Surgeon in 1906. Around 1889 he was helping his father to teach Medical Jurisprudence in Edinburgh.

[2] James Berry (1852–1913) worked as a hangman across the UK from 1884 to 1892.

[3] Kean was the alternative Irish surname which the Edinburgh Evening News (EEN) opted to use for Jessie King once she had been found guilty. Thanks to Tim Smith, who notes that the door of the condemned cell was removed to the Beehive Inn when Calton Jail was demolished in 1935.

[4] Jessie King’s attachment to her warders, and they to her, may be explained by common humanity and the awfulness of what was about to happen. Furthermore, the warders had been instrumental in preventing King’s several attempts at suicide. However, the journalist’s attention to this touching scene is also, arguably, a contrivance: an effort to reimagine Jessie King, to readmit her into the normal body of womanhood and conventional womanly behaviour. Elsewhere, the EEN journalist expressed disappointment and surprise at not being admitted to the execution chamber. His description is based on others’ eye-witness accounts.

[5] The description of Jessie's invocation of God’s blessing upon those participating by their presence in her execution, her implicit forgiveness of them, the pinioning of her arms and the binding of her legs, the commendation of her soul to Christ and plea for God’s mercy, the remarkable lack of death throes, the small black cross still clasped in her hand all evoke descriptions of martyrdom. The restoration of her Christian conformity, in the same way as the restoration of her conventional womanliness, is an important element in how this execution is interpreted, softened, and made reasonable to a readership which, despite the EEN’s occasional assertions to the contrary, was in many cases uncomfortable about the brutal reality.