THE STOCKBRIDGE MURDER CASE

1889

Part V

THE CROWD ON CALTON HILL

––––––––––––––

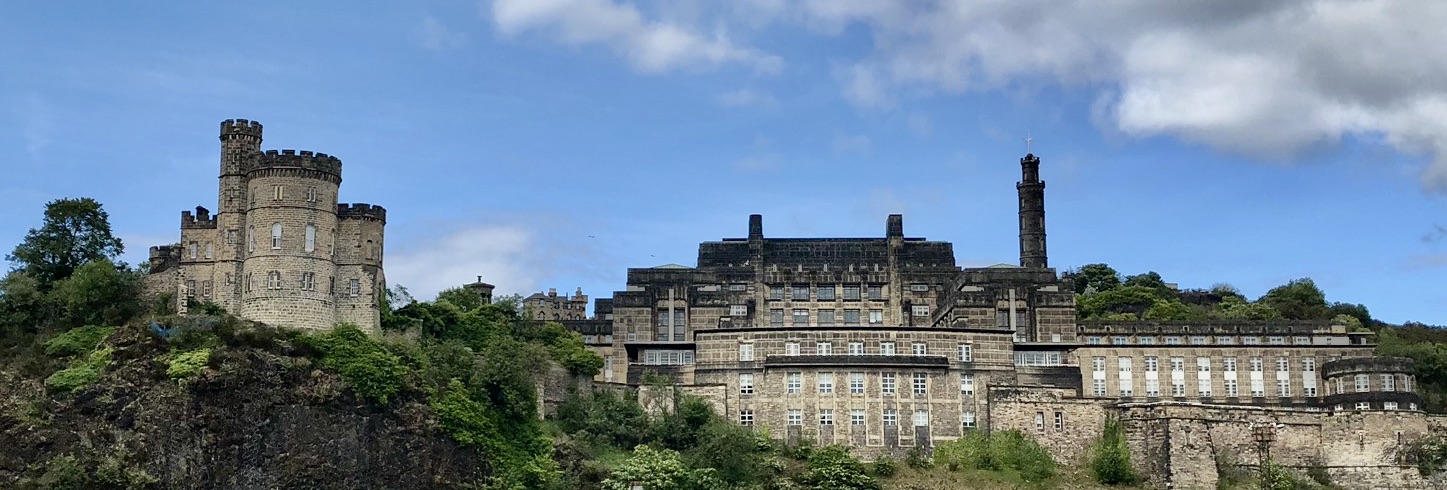

It is well nigh a generation and a half ago since executions stirred Edinburgh to the heart, and in these days of public executions the High Street of the city had a human block from the Tron Church to Castle Hill. Though conducted in strict privacy, the surroundings of the last penalty of the law have still a curiosity arousing desire among the lower classes of the city, and this morning when the signal of execution was hoisted about 1500 people had collected near the precincts of the Calton Jail.[1]

At the Chantrelle[2] execution a slight glimpse of the procession was caught by outsiders, who considered themselves lucky; but at the last double execution the view was screened.[3] On the present occasion every effort was made by the officials to disappoint, as the law commands, the motley crowd attracted by the event.

Yesterday afternoon the word that the execution was to take place got abroad, communicated to all by policemen, and hence it spread something like wild fire to the general public, who, candidly, it must be confessed, heard the news with subdued satisfaction. On the streets at night the death penalty was heard being discussed by the crowd, and the central point of view, the Calton Hill, and its advantages were loudly discussed.

The morning opened brightly, but there was a touch of frost in the air, while there was a good deal of ground mist. The first public stir was noticeable about an hour and a quarter before the time of punishment, and at that period a knot of ragged-looking men made their way to the Calton Hill, and took up position on the western side of the Nelson Monument, bearing two or three policemen company. A little later a stray reporter appeared on the scene, and was later on joined by two or three others.

A lamplighter perched on a lamp-post and a carter on a passing vehicle held a hurried conversation. “It’s between eight and ten,” said the carter. “Oh, no,” replied the lamplighter, “she’ll be gone at five minutes to eight.”

LIBERATED PRISONERS JOIN THE THRONG.

By two’s and three’s the crowd gradually swelled, and just after seven o’clock several females of low order emerged from distance. They glanced at the hill, and with one assent rushed towards the western stair of the hill, yelling, “Come on, we’re in plenty of time.”

The next feature was the arrival of city officials, and the most important comers were Bailie Russell, Dr Littlejohn, and the city officers. Their advent were eagerly watched by the crowd, who were profoundly ignorant of the whereabouts of the scaffold, though several asserted they could see its canvas covering. Their eyesight in this case, however, must have been of more than average strength. Not a view of the proceedings was to be gained, and the only reward gained by the early birds on the hill was a sight of those admitted crossing the prison yard.

In the meantime a dozen male prisoners left the jail, but they were by no means so well informed of the coming event or so eager for sight-seeing as their former unfortunate sisters. Only one or two directly made their way to the hill, while the others slouched along in their peculiar lazy style, making as much of their liberty as they could.

The type of people hanging about at this time was of the lowest kind, and their wait was anything but profitable, as they were visibly shivering. About 35 minutes to eight, it might be said, that the Canongate denizens began to appear, taking Jacob’s ladder as their course. But as they went up, two’s and three’s began to come down the hill, expressing disappointment at the scene as they beheld it. Then the first troop of genuine juveniles climbed a wall, and hurried on to the hill, followed by two girls aged about six and eight, who were the youngest of the crowd.

TOLLING THE BELL.

At a quarter to eight the prison bell began to toll, about every six seconds. It was audible a good distance from the prison, and might be heard all over the Calton Hill. Just then the people began to flock along Waterloo Place, coming in droves, and in ten minutes nearly a thousand had gained points of sight.

The crowd were of all sorts and conditions. The loudly-dressed bookmaker rubbed shoulders with the half-starved female, with her offspring at breast; but, generally speaking, the lowest strata of society formed the bulk of the representation. The slopes of the hill, the railings of Nelson’s Monument, the Russian cannon, and every knoll had a human covering, and with subdued looks all eyes were turned towards the flagstaff of the prison, newly freshened with white paint, and on the roof of the tower were stationed two officials, who watched for a token from below to hoist the death-signal. Every movement of these men, their kneeling or glances, was remarked on by the crowd, who strained their eyes vainly as eight o’clock approached.

The Canongate clock was heard clearly ringing out the hour, but yet there were few signs of the woman’s fate. Some people actually talked of bungling, and an irreverent youth exclaimed, “They’ll hang her by gun time.”[4] Two minutes past the hour the warders on the tower made a move, and with the utmost expedition they hoisted the black flag which fluttered in the breeze. There was a general exclamation, “It’s all over!” the public suspense gave way, and the younger portion of the crowd rushed down the hill, with an ill-concealed smile. The others quickly dispersed.

At various points of the city numbers of people awaited the signal on the jail tower. At Regent Road nearly a dozen carters pulled up their horses, and calmly awaited the flag. On the North Bridge and other points a crowd collected, and the jail being clearly visible, their morbid curiosity was easily satisfied. The flag floated over the jail for an hour.

Edinburgh Evening News, 11 March 1889

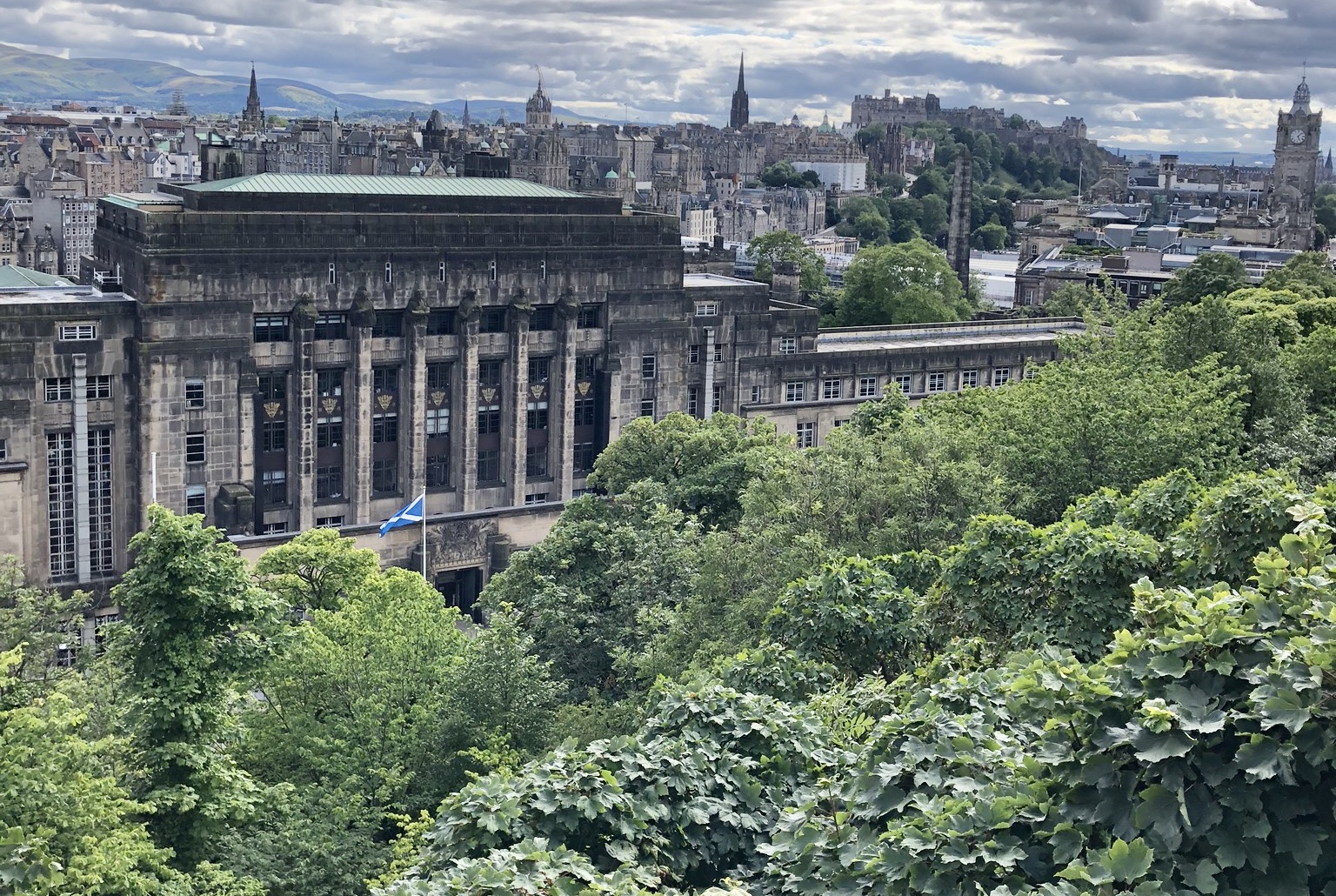

[Photos: R. Davis.]

[1] The Edinburgh Evening News coverage spins the fact that readers of the paper were participating vicariously in the same activity as the ‘lower classes’ outside the Jail. At least two reporters contributed to this account, although there is no acknowledgement of multiple authorship in the coverage of 11 March. Their description of the common people, and of the criminal types who emerged from and returned to them, is laced with contempt, disgust, and perhaps fear. The implication is that the crowd was moved by morbid curiosity and blood lust, rather than by a solemn duty to witness due process as enacted by middle-class officials and consumers of journalism.

[2] Eugene Chantrelle (teacher of French in Edinburgh) was hanged at Calton Jail for murdering his wife with poison in 1878.

[3] Robert Vickers and William Innes (poachers) were hanged on 31 March 1884 for the murder in Gorebridge of John Fortune and John MacDiarmid (gamekeepers). The bodies of Chantrelle, Vickers, Innes, Jessie King, and six others executed for murder remain buried under the western car park of the building which replaced Calton Jail: St Andrew’s House.

[4] The one o’clock gun time-signal fired from the Castle.