Searching for a bridge I was vaguely aware of, I found myself standing on it without knowing, writes Charlie Ellis.

The structure is the slightly mysterious ex-railway bridge that sits over the Water of Leith, connecting the site of the former Powerderhall Waste Transfer station with St Mark’s Park. Your judgement can be clouded by its dense fencing. I’ve often reconnoitred the area, but after each visit I feel the need to examine it again on a map. It’s not easy to make sense of. This area is dense with paths and routes, some well used, some known only to those in the know.

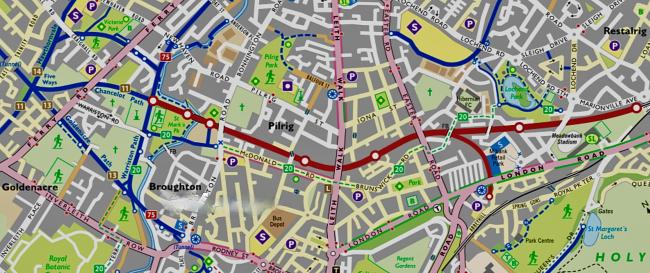

Map: Tim Smith.

As I neared the fence demarcating the southern end of the bridge, a gaggle of ‘youths’ were enjoying the sunshine. Puffing on something organic and pungent, they enjoyed nature. Concerned that I might get passively high, I made my way back.

After the ‘buffer zone’ at the far end of the track, the path narrows. Above you to the left sits the Craigroyston JFC football ground; below you to the right lies a group of well-sheltered allotments. Within a few yards you are back on the mainstream matrix of paths, with Chancelot Path extending in front of you.

Hidden nook

When I first stepped into this hidden nook in St Mark’s Park, I thought the line might still be active; it was so well preserved under the canopy of trees. Indeed, it was only in 2017 that the line was placed, by Network Rail as being ‘temporarily out of use’, usually the first in a series of official steps to formally close a stretch of railway.

At present, accessing this section is a little hazardous, with steep banking protecting it. Watch out in wet weather! St Mark’s Park is one of the key nodal points in the Edinburgh path network, linking the Water of Leith Walkway with National Cycle Route 75, part of the web of ex-railway paths.

As you look back it is notable that the rough section of path you’ve travelled along has no signage; a sense that exploring it is not encouraged. In fairness, it is currently a dead end. Will the railway path at Powderhall ever join the network? The idea of developing the disused railway line into an ‘active travel corridor’ has been mooted but currently seems to be in abeyance. Where would it take us?

Former glories

Let's start at the other end and work our way home. The back of Meadowbank Stadium is, these days, rather an unprepossessing place. Scruffiness abounds and wasteland waits to be transformed. Looking over the fence it's hard to imagine that this place was packed with cheering crowds in both 1970 and 1986, for the Commonwealth Games.

A British Movietone clip talks of ‘the giant Meadowbank Stadium … packed as some 2,000 athletes from the 41 participating nations enter the arena. It's a stirring procession with Scotland as the host nation providing some national colour’.

The 1970 Games evokes glorious memories, the 1986 games far less so. My Meadowbank memories go back to witnessing American sprinter Michael Johnson’s astonishing 19.85sec 200m on a windswept night in 1990. Former glories pervade the site. Meadowbank Stadium is not what it once was, though the rebuilt sports centre is now open.

The disused and neglected also offer radical potential, streaming into the future. Edinburgh is blessed with many great paths for ‘active travel’. It also has several potential paths as yet unrealised. Near the back of Meadowbank, on Marionville Road, there is a glimpse of one of these. An abandoned rail line extends from here to Powderhall, another sporting venue of the past. The Powderhall Sprint, the world's most famous sprint handicap race, was held at Powderhall Stadium for more than 100 years. In Discovering the Water of Leith (1988), Hamish Coghill reflects that the stadium was ‘likely to face major redevelopment after being sold in 1988’. Instead, it was swept away and housing built instead.

Bridge of Doom no Brigadoon

On a cold winter’s day, the line at Marionville Road looked bleak and forlorn, the rails rusting, and trees shorn of colour encroaching upon the line. Closing my eyes, I imagine myself trundling along it, looking up at newly built brick flats as the path makes its way west towards Easter Road.

To get there it passes under Crawford Bridge, also known as the 'bridge of doom', synonymous with football violence in the 1980s and 1990s. Stories abound of ‘casuals’ forced to jump from the bridge into the overgrown ravine below.

The potential path would then run under Leith Walk, beneath where the Leith Walk Police Box sits. Peering over the edge you can see the line heading inexorably towards the chimney of Shrubhill Power Station. This was itself part of another lost transport network, the cable-tram system.

The final leg of the journey would take you past the fast-changing Shrubhill area, towards Powderhall – which too is in the process of redevelopment. The line then crosses the Water of Leith. Its final rusting rails lie in the undergrowth surrounding St Mark's Park.

Leafing through an old book (An Illustrated History of Edinburgh Railways), I find a photo and description of the original Powderhall Station and the way ‘the track dips down to a bridge over the Leith Water, to rise thence past the woodland of St Mark’s Park, where the lines to Bonnington and North Leith diverged’. I love the old-fashioned ‘thence’ and also the description of the river as ‘Leith Water’; they transport the reader back in time.

There is a range of possible routes which start and terminate here on this bend in the Water of Leith. The area has not always been a wee green space of woodland, football pitches and allotments but was once dominated by the vast Chancelot Flour Mill, closed in the 1950s and finally demolished in 1972 (the company relocating to Western Harbour). All part of Edinburgh’s industrial heritage, often neglected in contemporary descriptions of the city. Powderhall itself was so named due to gunpowder production.

If the dream of the Powderhall railway line becoming part of the cycle network is ever realised, it will add another key piece of the communication lattice in the north of the city. It will further aid those who wish to traverse the city avoiding traffic. The ability to do this is one of the great joys of Edinburgh. Were this path to exist, it would form a natural link with Lochend Park – on the day I visited, resembling a mysterious primeval swamp – and the Restalrig Railway Path.

Avoiding traffic is what draws people to these paths. They offer so much to those who live in and visit Edinburgh. The new link being formed at Russell Road will allow even more seamless travel across the city. Were the Meadowbank to Powderhall link to be realised, this would further free the city, making even more journeys possible unaffected by road transport.

Edinburgh Council’s Active Travel Action Plan 2030 lists this link (‘new path along former rail line from Lochend Park area to St Mark’s Park’) as a scheme that might be ‘delivered post 2026’. Will the past be the future? We shall see.

Charlie Ellis is a researcher and EFL teacher who writes on culture, education and politics.

For previous Spurtle coverage, see 'Slow Progress' and Issue 291, p.2. We understand a promised feasibility study by Council officials, which was delayed during Lockdown in favour of Places for People priorities began in earnest in October 2023.